What About 2012?

Dr. David Stuart, archeologist and Schele Professor of Mesoamerican Art and Writing at the University of Texas-Austin, speaks out on the subject.

Long before Galileo tracked heavenly bodies in the 17th Century, the Maya watched the skies and developed a construction for time. What did they really say about 2012? “Absolutely nothing,” says Dr. David Stuart, archeologist and Schele Professor of Mesoamerican Art and Writing at the University of Texas-Austin. He calls the current frenzy that the world will end or be radically changed on December 21 “complete nonsense” and suggests that New Age writers and Hollywood producers have melded traditions into “one pan-Meso-american hodgepodge, taking the specificity of the 2012 date from the Maya and grafting it onto the Aztec imagery of world destruction.”Stuart began exploring Maya ruins at the age of eight. He lived in a thatch house in Coba, Mexico with his parents while they studied and mapped ancient Maya sites in the jungle for National Geographic. Remembering the excitement around discovery of a broken stone slab, he wrote, “I was forever hooked on Maya archeology.”

“The truth is, no Maya text—ancient, colonial or modern—ever predicted the end of time or the end of the world.”

Reading The Order of Days: The Maya World and the Truth About 2012, Stuart’s latest book, can be mind boggling. He speaks of octillions and septillions of years—and that’s not all. “The Maya conception of time will end eons after our solar system has burnt itself out and the universe is no more.” The book is based on what ancient Maya records had to say about time and the workings of the cosmos and their place within this complex world view. It is not to critique theories about Maya astronomy or 2012. Where did these ancient Maya records come from?

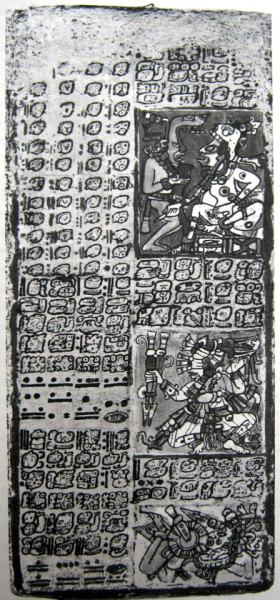

An 800-year old Maya book, now called the Dresden Codex, turned up in Germany. How it got there remains a mystery, but it sat virtually unnoticed until 1880, when a fascinated librarian picked it up and became obsessed with figuring it out. About 10 years later he did; he cracked the bar-and-dot code of noting time, opening the doors to study and understanding of other Maya hieroglyphics. The irony, Stuart laments, is that just when decades of hard work in the field and libraries is paying off, much of the hubbub about 2012 is “by gurus and spiritualists who wouldn’t know a Maya glyph if one hit them on the nose.”

Briefly, as a sort of 2012 for Dummies guide, the code reveals a base date of 3,114 B.C. from which to mark the present era. This, in fact, predates the Maya by two and a half millennia and was invented by an earlier group, perhaps the Olmec. The Maya measured days, months, 260-day years and periods of time, one of which is 5,000 years. Figures—hieroglyphics—represent the measurements.Yet, “2012 isn’t just another period ending… but a very special date indeed.” The Maya called it a “fold in time,” the end of one era,the beginning of another.

The Maya recognized a cyclical system of time; one period ends and another begins. History repeats itself, if you will. Thus, prophecy is merely a reflection of events and trends of the past, an exercise in “pattern recognition,” says Stuart. This is not unlike what is written in the Biblical book of Ecclesiastes: “What has been will be again. What has been done will be done again. There is nothing new under the sun.” That said, it could be argued that the cyclical perspective could result in self-fulfilling prophecy, actions determined by a perceived future.

Perhaps an example of the cyclical system is ancient Jewish tradition. Land was worked for periods of six years, then allowed to rest the seventh. The Jubilee year occurred every seven periods, the 50th year. At that time all property was returned to its original owner; debts were canceled; slaves were freed. The idea was that everything belonged to God, who loaned it to His people. In recognition and honor of this, all must be returned periodically.

The cyclical view may have been particularly fitting for an agricultural population. The concept of time as linear may be preferred in modern thought as a notion of progress. In fact, Spanish priests had a hard time accepting the power of the calendar in the daily lives of the people, banning it as witchcraft and superstition. But the Maya continued to use their calendar for hundreds of years after Spanish evangelization, albeit secretly, to give meaning to their lives, politics and rituals.

Calendars are but a tool for organizing time and experience, based on observed astronomy and alternating periods of light and dark. They have undergone changes over the centuries, ever trying to get it exactly right, but are still inaccurate and “messy,” as Stuart calls it. There are still months with 30 days and some with 31, and then there’s that extra day in February every four years.

In truth it would be difficult to separate linear and cyclical systems of time. A year progresses from January to December—linear. But then it starts all over again in January, repeating itself—cyclical. Stuart explains, “A key difference between linear and cyclical times comes down to whether one considers the progress of time to be a simple one-way street or capable of accommodating more complex notions of multiple beginnings.”

Stuart emphasizes that, as the Maya become less mysterious, the reality of their accomplishments is more impressive than what, if anything, they had to say about the future. “They deserve better than that,” he writes in his book. There is only one specific reference, carved in stone in Tortuguero, Mexico, that marks the end of a period that corresponds to December 21, 2012. But beyond that, according to Stuart, it says nothing about any catastrophic or otherwise meaningful event to happen at that time. It’s not the first time the drama of a new era has been predicted. To mention one, the year 1987 would supposedly usher in a new era of world peace and harmony. Hmmm.

So relax. Stuart is reassuring. Ignore doomsday theories. Celebrations there will be. Big ones. For the Maya, December 21, 2012 will indeed mark a fold in time, not an end but rather the first of many future repetitions.

Dr. David Stuart remains actively engaged in several large-scale excavation projects in the Maya area.