Uncovering the Art of Francisco Goldman by Mark D. Walker

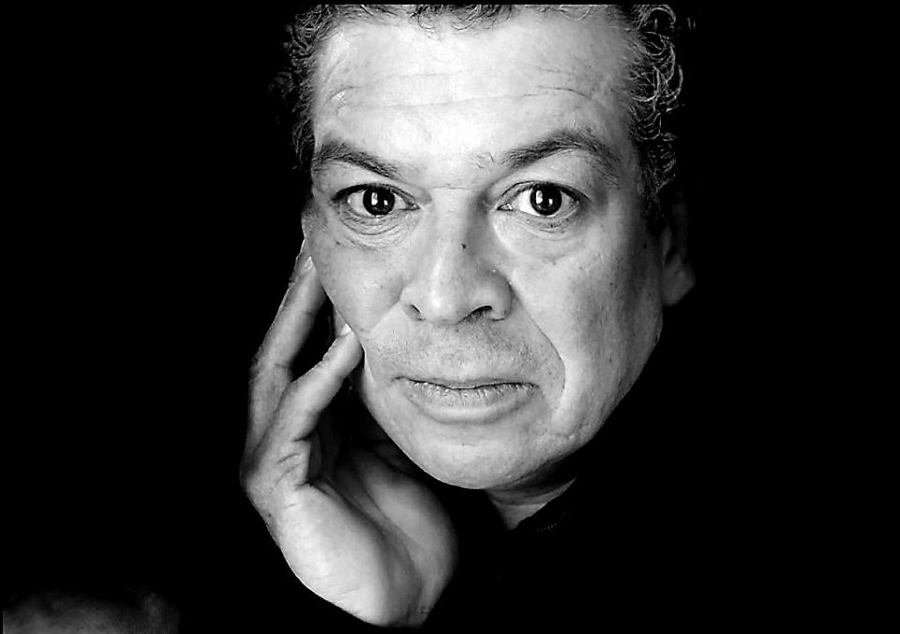

The recent HBO documentary, The Art of Political Murder, introduced a growing number of readers to the author of the book on which it’s based, Guatemalan American writer Francisco Goldman. Given his background—Guatemalan mother, Jewish-American father, formative years growing up in rough and tumble Boston—Goldman has a unique insight into the violent history of Guatemala and what makes the country tick. The HBO documentary closely follows Goldman’s book, a thorough dissection of the sensational murder of Guatemalan Bishop Juan Gerardi in 1998. Days before his brazen murder, Bishop Gerardi published a detailed account of the country’s military involvement in the atrocities committed during Guatemala’s civil war.

I was drawn to the author because, like Goldman’s father, I married a Guatemalan woman. Like Goldman, my wife and our children bridge two cultures. And, like any culturally diverse family, there’s always the sense of being somewhat of an outsider in both cultures.

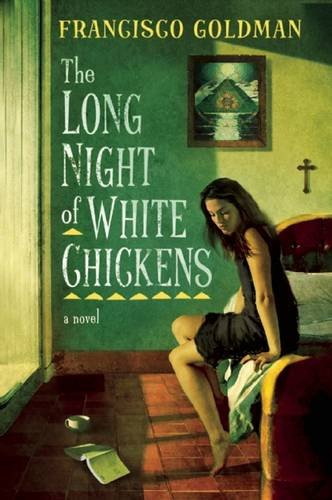

Goldman’s debut novel, The Long Night of White Chickens, published in 1992, foreshadowed some of the themes that piqued his interests—both as a journalist writing for top tier magazines like Harper’s and the New Yorker, and as a novelist.

In the novel, Goldman draws from his own experiences. The protagonist, Roger Graetz, is raised in a Boston suburb by a matriarchal Guatemalan mother. Into the household enters Flor de Mayo, a beautiful young Guatemalan orphan sent by his grandmother in Guatemala to serve as a maid. Years later, Flor is murdered in Guatemala and Roger, devastated by the death of someone he secretly loved, travels to Guatemala to uncover how and why she was murdered. With the help of a childhood friend, he ventures on a quest to find Flor’s murderer, a fascinating investigation in which myth intermingles with reality.

Goldman’s attraction to this storyline reflects his interest in the Central American wars he covered in the 1980s as a journalist for Harper’s Magazine. As he says in a Lit Hub interview, “Sometimes people want to mystify where novels come from, but often novels come from the obvious source, simply what the writer is most persistently thinking about.”

The San Francisco Review of Books said of the novel, “Not since Nabokov’s infamous Lolita or Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon has an author displayed such mastery of contemporary literary methods.”

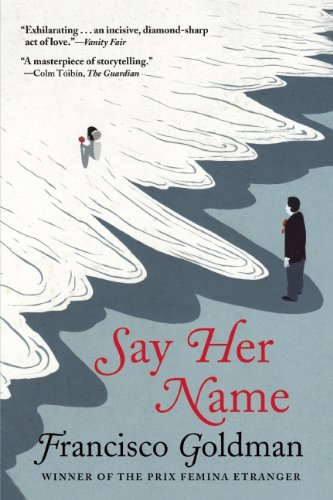

Say Her Name (2011), Goldman’s second novel, is an evocative story of love and loss, also autobiographical. Goldman had married Mexican writer Aura Estrada but, tragically, a month before their second wedding anniversary, Aura died in a surfing accident. To exorcise the madness of grief and guilt, Goldman wrote a novel that creates a moving portrait of his love for Aura and utilizes humor and humility to lighten the pain he was experiencing due to her death.

In the novel, he has a visceral reaction to a dream in which he has a conversation with Aura’s spirit:

…I woke before dawn to find Aura stretched out beside me in our bed, nearly invisible, a lighter darkness within the darkness of the room but with her distinct shape…. Did you just come in from the tree? I asked Aura. No, she said. Mi amor, that’s your imagination. Pobrecito, she giggled. Why would I want to hide in a tree in the middle of winter? So this is my imagination, too? No, this is me. Of course, it is. Aura, do you promise? Si, mi amor, it’s me. I don’t get it. If you can visit me like you are now, then why don’t you come all the time? I’ve been so lonely without you. We’re not allowed out that often, she said. If I were here all the time, then I would be a ghost, and I don’t want to be a ghost. Ghosts suffer. That makes sense, I said. And, I thought, it really does make sense. But with that, Aura was gone, dispelled back into the air, into the chilled early morning light?

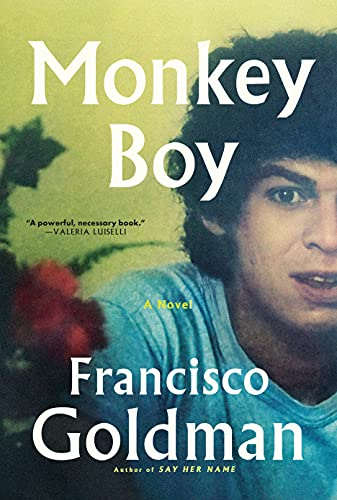

The blend of Yankee investigative reporter and Latin mythmaker is an important element of Goldman’s most recent book, Monkey Boy (2021), which delves into his personal reflections on growing up in Boston, the quiet dark-skinned boy sitting in the back of the class, the “monkey boy.” Like The Long Night of White Chickens, it is designated as a novel, rather than an autobiography. In a revealing interview with Rachel Kushner for Lit Hub, Goldman explains the importance of changing the surname “Goldman” of his lead character:

So, yeah, that “-man” to “-berg” [Goldman to Goldberg] makes a big difference. It’s a first decisive step into fiction, into turning myself into a character that’s going to move and act and think within a fiction. It’s freeing myself from “myself,” from any duty to be faithful to the “known facts,” as I might be if I were writing an autobiography, even if many of the components I may be giving to “Frankie Goldberg” are, in fact, drawn from my own life.

Walking the fine line between literary fiction and autobiography, bordering on realistic realism, gives the author flexibility to fill in gaps with fictional material that enhances the story. In an author interview published in “Identity Theory” magazine, with Robert Birnbaum, Goldman claims that he agrees with Henry James that the historical novel is humbug. Henry James was referring to the historical novel where people believed you could have a realist historical novel.”

In the Lit Hub interview, Goldman explains the key role that several women play in the story—Aura, his mother, his sister, and his grandmother:

There’s also my Guatemalan grandmother, Abuelita, definitely a strong and eccentric woman who I adored, and the women she sent up to Boston to help my mother with housework and looking after us so that she could go to college, eventually becoming a college Spanish professor.

In Monkey Boy, Frankie Goldberg visits two of these women:

As an adolescent, I had a talent for turning unrequited loves into friendships. Later my friendships with women didn’t require such painful beginnings. All my adult life, I’ve had strong male friendships, too, in the U.S., in Mexico, and Central America. But in the U.S., most of my closest friends are women. I guess I just enjoy their conversation and sense of humor and way of being in the world more, and I think I also relate to them more.

Jewish-Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg helped Goldman learn one important lesson related to his roots in a diverse, cultural background: “how artificial the racial and ethnic categories we’re boxed into are, and that there’s no such thing as being ‘half and half’ anything, that we’re only fully what and who we are.”

Goldman reveals interesting connections between his family and friends and key events in Guatemala’s history, and shows how he can speculate about what might have been by fictionalizing his personal experiences and understanding based on his years covering Guatemala’s corrupt elite class, army, and politicians:

Did the United Fruit bilingual secretary, Lolita Ojito, ever filch a note or diary page in which Freud’s nephew had scribbled something like “If this is gonna work, boys, we gotta get the archbishop on board, and pronto” and bring it to her best friend in Our Lady’s Guild House, so that she could give it to the consul, who would pass it directly to President Arbenz, maybe in time to save the day? Doesn’t seem so. At any rate, the day was never saved. Questioning Mamita [the author’s mother] about the coup had turned out to be futile. If only I’d thought to ask her about it years ago. If only.

The speculation is even more compelling when the author reveals that his mother knew the ambassador, Cabot Lodge, and the upper crust Bostonian “Brahmins” who were employed by United Fruit Company.

This book is powerful on many levels and provides additional insights into the author’s previous works. As Publishers Weekly correctly enthused, “Captivating…Goldman’s direct, intimate writing alone is worth the price of admission.” And Kirkus’s starred review joined in, “The warmth and humanity of Goldman’s storytelling are impossible to resist.”

Friend and fellow author, Tom Miller, an acclaimed travel writer (The Panama Hat Trail, among many), has held Goldman in high regard for years. Miller revealed that one of Goldman’s essays was included in his compelling anthology of accomplished Latinos and their lessons about learning English and learning about life. Goldman’s piece is entitled Ghost Boy, and sheds light on what he refers to as his “binational” identification.

Goldman reveals that he spoke fluent Spanish as a four-year-old, but by the time he reached college, he only spoke English:

The little boy who at some point must have been able to speak both had been cleaved in two: one who spoke English, and the other – vanished! A permanent absence. I was his ghost, and he was mine. In a sense, I’ve spent the last three decades, during which I’ve lived as much in Latin America as in the United States, as if on a mission to bring those two boys together.

The author tells of the pressure from school administrators in Boston to speak only English, “What kind of country produces educators who think it necessary to exorcize foreign languages and accents from little children?” He goes on to reflect on a Cuban writer friend’s challenge finding an adequate translator for his novel. “Wasn’t the United States the richest, most powerful nation on Earth? Then how could it have such incompetent professional literary translators?” He pondered that question and told his Cuban friend, “It’s because we’re the nation we are, so rich, and powerful, that we have such incompetent translators.” He sounds a warning at the consequences of this reality: “A country that speaks to the world only in its own language and describes reality to itself only in its own language will be able to convince itself of anything.”

Goldman would overcome this limitation after covering Central America’s wars in the 1980s and 1990s as a freelance journalist:

I’m a fairly fluent Spanish speaker again, just like when I was four. For years, my mother and I have spoken only Spanish to each other. To get my Spanish back took a long time and an enormous commitment. To borrow a certain literary metaphor, it was like constructing my own garden of forking paths that I can follow back into the past, to a place where that lost boy and I were never separated, and forward into a familiar landscape where two separate countries comprise one.

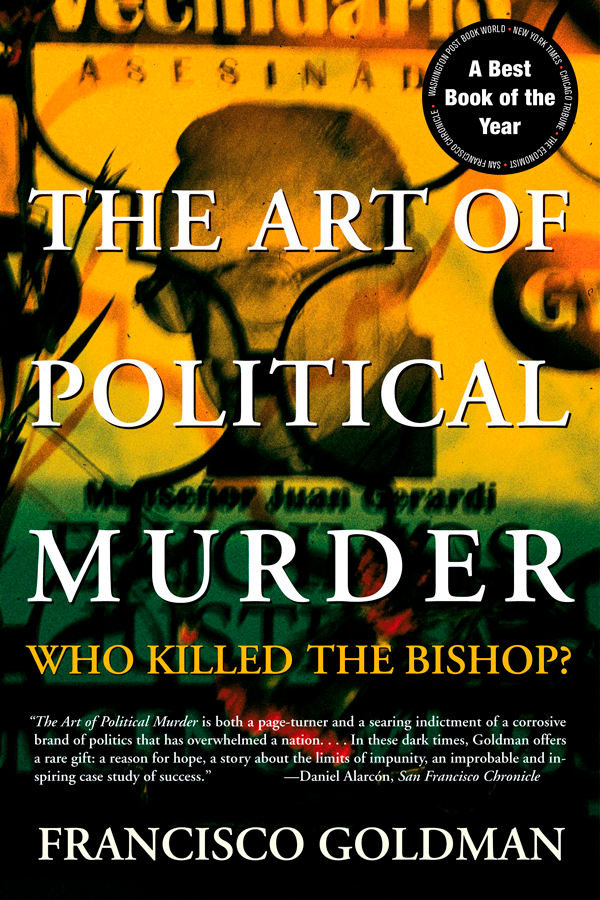

Goldman’s book The Art of Political Murder, published in 2007, reflects the fruits of his hard work, as well as insights informed by his coverage of the wars in Central America in the 1980s as a contributing editor for Harper’s Magazine. Initially, Goldman thought he was just going to write “a short book on the Bishop Gerardi murder case, a work of journalism,” but it turned out to be so much more. For me, it represented an almost surreal detective story that opens the door into the Latin American reality of State Sponsored assassinations and organized crime.

The book is a non-fiction account of the assassination of Guatemalan Catholic Bishop Juan Jose Gerardi Conedera in 1998 by the Guatemalan military, an expansion of an article he wrote for the New Yorker. In all, Goldman spent seven years of painstaking and often dangerous investigative digging for the book. Rachel Kushner, who interviewed Goldman for Lit Hub, characterizes the author as “a brave and storied journalist who has risked his life to speak truth to power—supergonzo.”

Bishop Gerardi was Guatemala’s leading human rights activist and was bludgeoned to death in his garage, only a few hundred feet from the government’s most sophisticated security units and surveillance apparatus. This took place only two days after a groundbreaking church-sponsored report was released, implicating the military in the murders and disappearances of some 200,000 civilians.

Goldman tells how the Catholic Church formed an investigative team comprised of secular young men in their twenties known as “Los Intocables” [The Untouchables]. The murder was known in the tabloids as “The Crime of the Century.” Corruption was apparent at all levels: the expected lack of interest of police investigators, and the inability of the existing legal system to deal with the crime. In what would be his first non-fiction book, Goldman managed to reach and interview witnesses that no other reporter or authority was able to access; he witnessed first-hand some of the crucial developments in the case unfolding before him.

Goldman’s investigation reveals the involvement of several United States administrations in creating some of the circumstances that led to the bloody Civil War. They were a consequence of a coup engineered by the CIA in 1954 against Jacobo Arbenz, only the second democratically elected president in Guatemala’s history. This reality was confirmed with a remarkable apology by President Bill Clinton on a visit to Guatemala in 1999, according to a passage in The Art of Political Murder. When sitting next to stone-faced President Alvaro Arzu, he said: “It is important that I state clearly that support for military forces or intelligence units that engaged in violent and widespread repression of the kind described in the report was wrong…and the United States must not repeat that mistake.”

Goldman takes the reader through Guatemala’s byzantine legal system and describes the constant threats against judges and witnesses (several of whom had to leave the country, fearing for their lives). Many of the rulings on the case were flawed; for example, in the Fourth Court of Appeals, where important witness records were not even requested by the appellate judges.

Finally, in January of 2006, the author received a confirmation by email that the Supreme Court had upheld the convictions and thirty-year sentences for several of the perpetrators. Goldman, at hearing the news, felt astonished yet relieved, but attempts to limit and delay the convictions went on until April of 2007, when a new judge took over as President of the Constitutional Court. Not until April 25th–the day before the ninth anniversary of the murder of Bishop Gerardi—did the Public Ministry give notification that the guilty verdicts against the Limas (military officers who planned the assassination) and Father Mario Orantes (a Catholic priest who was complicit in the murder) had finally been upheld. And only after the convictions were upheld did Goldman feel he could move ahead with The Art of Political Murder.

In an interview for Lit Hub, the author describes why his perspective is unique,

The protagonists of that historic catastrophe are Central American; they’re the ones who lived and overwhelmingly gave their lives, who survived and endured even if gringos were responsible for so much of that nightmare. You’ll notice, if you read Bolaño or Castellanos Moya, that they never commit the gaucherie, if I can call it that, of explicitly blaming the U.S. for the violent political catastrophes depicted in some of their novels, even though of course they know what happened. They’re “our” stories. But an American like Deborah Eisenberg is writing for an American audience; she’s performing a brilliantly subtle and deeply felt sort of assault on conscience and obliviousness. An essentially binational writer like me is pulled in both directions.

Epilogue

After several years of reading and reviewing Goldman’s books, I’ve been increasingly impressed by his considerable talents as a writer and his unique insights into the realities of Guatemala and Central America. I recently learned from an author friend that, at one point, Goldman had been considered for a MacArthur “Genius Grant.” But the real impact and legacy of the author is most obvious in the many ways people have tried to reproduce his work for an ever-growing audience.

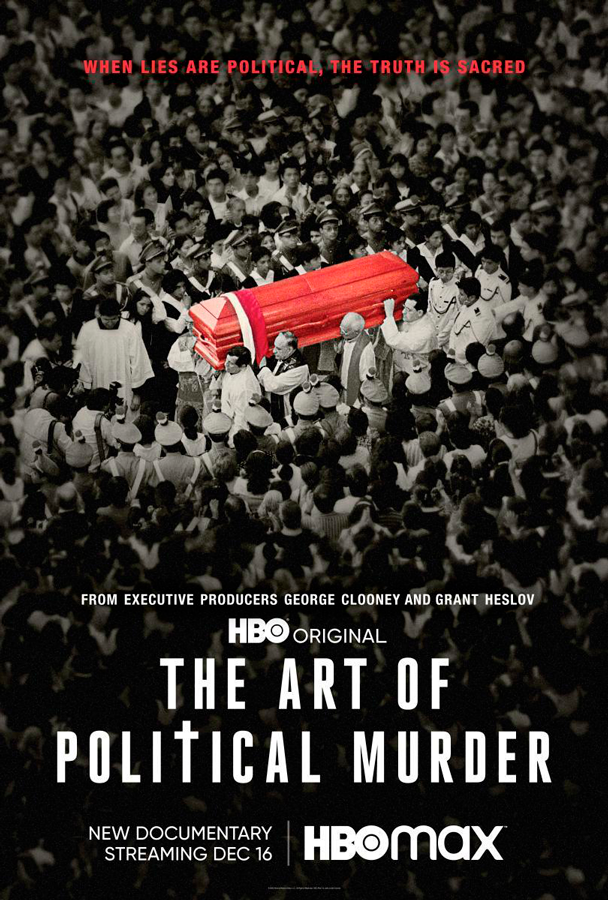

Below is a link to the HBO documentary The Art of Political Murder (based on Goldman’s book) which premiered late last year and has been nominated for an Emmy. The documentary clarifies a very complex storyline that probes multiple layers of the reality of power and corruption in Guatemala. Produced by George Clooney and Grant Heslov, the film includes dramatic interviews with key witnesses, investigators, and the prosecutors.

We learn about the theories of who killed the bishop and why. Among these theories: organized crime, drug traffickers, church thieves; it was even proposed that it was a crime of passion. Not only does the film chronicle the police investigation, it also closely follows the more fascinating investigation of the investigation. It’s an exploration of the crime and its aftermath – including governmental and military corruption, and more attempted violence.

Most of the film focuses on what happened after the murder: a botched crime scene, numerous theories, citizen protests, and a high-profile trial. It’s really the stories behind the story. The bishop was an outspoken activist for the Mayan people, and he was beloved by many. The revelations brought to light about the police investigation leave you wondering what kind of government would issue a state-sponsored hit on a religious leader of the people.

But the bombshell in the courtroom was a homeless witness, Chantax, who revealed that he wasn’t homeless; instead, he was an undercover informant tasked by military intelligence with spying on Bishop Gerardi. Moreover, on the fateful night in question, he had been recruited by three army officers to help with the crime. The trio received 30 years behind bars, while Father Mario Orantes got 20

.

After you view the film, check out the conversation on YouTube hosted by Director Paul Taylor with author Francisco Goldman, investigator Arturo Aguilar, and Guatemalan journalist Claudia Méndez Arriaza. They talk about the making of the film, the impact of Bishop Gerardi’s murder, and updates surrounding the case.

Uncovering the Art of Political Murder HBO

When asked what his great takeaway from the film is, Goldman reflects on how justice and democracy must be fought for. People often talk in platitudes about “fighting for justice,” but, in fact, it takes the little guy, the common person in the street like the “homeless” witness, Chantax, to step up and speak truth to power. The small guy needs to “step up and take a risk and have the courage” to fight back when justice and democratic rule are under attack. He points to the main investigator and the Guatemalan journalist as being the real heroes as they are still in Guatemala, possible targets for reprisal.

When questioned about the ongoing efforts to bring about justice and transparency in Guatemala, Goldman points out that for progress to be made, local judicial institutions need support from their international counterparts. Without outside support, intimidation and violence will continue to stifle real justice. According to Goldman, the day in 2015 when ex-general President Otto Perez Molina went from the presidency to prison was one of the great triumphs in combating corruption. But he goes on to say, when former Guatemalan President, Jimmy Morales, and former President Trump both tried to destroy the very foundations of the justice system in their respective countries, the battle is not over.

The HBO production also produced a historic timeline for those not familiar with the history of Guatemala, the impact of the U.S., and the circumstances leading up to the tragic assassination of human rights activist Bishop Gerardi.

The Art of political murder Timeline

Although the MacArthur “Genius” award never materialized, he did receive a 2017 Barnes & Nobel Writers for Writers Prize, and PEN Mexico’s 2017 Award for Journalistic and Literary Excellence. Also, he has been a Guggenheim Fellow, a Cullman Center Fellow at the NY Public Library, and a Berlin Fellow at the American Academy of Arts. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In addition to his five novels and two books of non-fiction, Goldman has written for the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, Harper’s, The Believer, and many other publications. He directs the Aura Estrada Prize auraestradaprize.org.

Recently, I asked Goldman to be interviewed for a documentary I am co-producing, Trouble in the Highlands. Many of the stories will be narrated by, and understood through, the eyes and perspective of Guatemalan indigenous leaders. Goldman will be part of a diverse team that includes prominent indigenous academics and activists, an award-winning journalist and media producer, a former NGO (non-government organization) executive/writer and a seasoned videographer/director.

“I think everything you are, everything that engages you, eventually comes to bear on the novel you write. I think the creative energy in novel writing, obviously, comes from tension. From trying to fuse. From trying to make coherent disparate things that might not at all seem to belong together within a narrative.”

— Francisco Goldman

“I’ve written one book-length piece of journalism. The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed Bishop Gerardi? That book had an impact. Eight years after it was published, it’s still having an impact in Guatemala. I remember when I wrote it, a surprising number of people said things to me like, ‘That is such an amazing story; why didn’t you turn it into a novel?’”

— Francisco Goldman

About the author Mark D. Walker

(MillionMileWalker.com) Mark Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala,1971-1973, working on fertilizer experiments with small farmers in the Highlands. Over the next 40 years, he managed, or raised, funds for many international groups, including Food for the Hungry and Make A Wish International and wrote about those experiences in Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond. He is also a contributing writer for Revue Magazine: Tschiffleys Epic Equestrian Ride; The Future of the Peace Corps in Guatemala; Maya Gods & Monsters; The Making of the Kingdom of Mescal; Luis Argueta – Telling the stories of Guatemalan Immigrants; Luis Argueta: Guatemalan Filmmaker Recipient of a Global Citizen Award; and Traveling in Tandem with a Chapina. His wife and three children were born in Guatemala.

Go to MillionMileWalker.com or write the author at Mark@MillionMileWalker.com

REVUE magazine article by Mark D. Walker