The Jewel in the Crown

- Antigua’s central park by César Tián

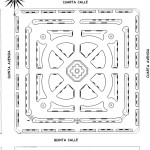

- Architectural drawing of the Parque Central by Abner Saul Quinac

- 1940 photo of Antigua’s central park by Stein (courtesy of CIRMA)

- 2010 Antigua’s central park by César Tián

- Plaque commemorating the designer of the central fountain, Diego de Porres (photo by Rudy Girón)

- The original sirenas (mermaids) from the park’s fountain are at the Museo Santiago (photo by Rudy Girón)

- During the Christmas holidays the park is illuminated with thousands of ornamental lights. (photo by Rudy Girón)

- During the renovation of the park in 2000 the gardens were improved, smaller benches replaced the old cement ones, and wrought-iron fences were put around the planted areas. (photo by Rudy Girón)

What started as a blank square in the original drawings, La Antigua’s Parque Central grew and morphed in fits and starts for 467 years to meet the needs of each new generation.

Written by Judy Cohen

My interest in the design of La Antigua’s central park was sparked in the defining moment that I focused on the shape of the planting areas, which are vaguely geometric and, like puzzle pieces, rounded at the edges. There is one puzzle piece on one side of a path and another exactly like it—or close—on the other. If I walk across the path following the straight line of the pavers, the pieces will meet.

Symmetry, they say, is harmonious and beautiful. Dropped randomly, these planting areas would be a chaotic jumble. Instead everything is measured so precisely that the effect of the rounded edges of the curbs, the wavy branches of the trees, together with the curved walkways and walking circle around the fountain, creates a small masterpiece. My first thought was that a renowned landscape architect designed it in one piece, but no—it didn’t happen that way at all.

Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala (later renamed La Antigua Guatemala) was founded in 1543. This year lies in the blurry timeline when the late Middle Ages changed into the Age of Discovery. The conquistadors followed hard on the heels of Columbus to the new world, driven by gold fever and the desire to conquer. They earned their name.

Only 51 years had elapsed between the time Columbus landed and the founding of the third Guatemalan capital. The first two sites were abandoned as unsuitable. Early settlers had already learned hard lessons about natural disasters in the new country; earthquakes first, and then floods and mudslides, which destroyed the second capital. They prayed the Panchoy Valley, only a few miles away, would be far enough from volcanoes to keep them out of danger. The new location was flat, beautiful, had plenty of water, lumber, clay for adobe bricks and rich soil.

Juan Bautista Antonelli was the Italian military engineer appointed by the crown to design the new town. He used the grid system with the avenidas north, south and the calles east, west. The town plaza was placed in the center. What we now know informally as Parque Central was founded as the Plaza Mayor, Plaza Real or Plaza de Armas. It started as a blank square on Antonelli’s drawing and grew and morphed in fits and starts for 467 years to meet the needs of each new generation.

The Plaza Mayor was a busier and more exciting place in other centuries than it is now. It was the center of all public activities: entertainment, markets, public events, parades and religious ceremonies. They even staged horse races and bullfights on special occasions. Water was piped in for the horses in 1555, but there was no central fountain until 1738. And: “Every so often a military parade took place, hence ‘Plaza de Armas.’ The ladies would dress in their most flouncy frocks and petticoats, uncaring of the mud that ruined all the hems, and crowd around the Plaza in billowing skirts that echoed the surrounding arches.” —Antigua For Life, Barbara Belcher de Koose, p. 62.

In the only painting of it in the 17th century (1678), we can see the marketplace, which the city fathers had to organize into some kind of order so horses and carriages could get through. Still no formal streets.

In Europe (1400-1800) law and order was established and punishment carried out in public squares. The conquistadors brought this practice to Central America. Hangings, whippings, and the stocks were used to enforce order. Looters were hanged and people whipped for trivial offenses.

The park went through the same ups and downs as the town. If the town suffered earthquakes and floods, the plaza was neglected. In careless times, people broke the fountain, cut off the heads of the original sirenas (mermaids) designed by Diego de Porres in 1738 and threw them on the rubble heap. When the town prospered, the square prospered, too. Needed repair work was done, trees were planted and rubbish removed.

Few cities have fought as hard to stay alive as Antigua. There was an almost continual push by the forces of nature to destroy it. At the same time, dedicated and stubborn people through the ages fought to pull it back from disaster. Despite the optimistic hopes of the first settlers, Santiago (later La Antigua) was not safe from nature’s might. Between 1520 and the end of the 19th century, 50 major eruptions of Fuego occurred. In 1773 a massive earthquake hit and the Spanish king ordered the city evacuated, although it had recovered from a devastating one in 1717 and rebuilt.

Following a major flurry of building called The Golden Age, the 1773 quake destroyed the most beautiful churches, convents, monasteries and private homes in one day.

Afterward the capital was officially moved to Guatemala City, along with all the wealth that could be carried on the backs of Indians or carted away in wagons. As much or more damage, they say, was caused by salvagers as by the earthquake itself. Citizens were threatened with jail if they didn’t leave.

However, the community was never quite abandoned. From being the acknowledged capital of Central America and a bustling, vibrant church-oriented city, it lapsed back as a quiet village again and was renamed La Antigua Guatemala.

When the modern age dawned, the charming, colonial city of Antigua, for the most part, was buried under mud and rubble and forgotten. Not by everyone though. Knowledgeable people knew that a gargantuan job of restoration could restore it. Fortunately, since it was now off the beaten track and in a known earthquake area, Antigua didn’t suffer the same fate as Lima, Peru and Mexico City, where many remaining beautiful colonial homes and artifacts were destroyed to build high rises in the name of progress.

Coffee brought a degree of prosperity to the valley in the late 1800s. Dedicated people realized they also had a treasure in the colonial city lying under a lot of mud and rubbish. They began to dig it out and protect it.

The park went through a major renovation in 1936. The sirenas in the fountain were restored by Oscar González Goyri; the rusted shaft from 1738 was cleaned and restored. Water flowed once more. A series of proclamations came out: In 1940 Antigua was declared a Protected City, which saved many of the beautiful old colonial houses from being torn down. Buildings were limited to two stories.

In 1944 Antigua was protected further when it was declared a National Monument. Modern buildings were barred. However, billboards and neon signs crept in, and other debris of the 20th century littered the narrow streets.

Once more in 1976, a major earthquake struck. It destroyed most of the renovation efforts. Over 20,000 people were killed and a million were left homeless in Guatemala. In Antigua, most of the renovation and digging out was destroyed when the charm of the old city had just begun to emerge. This seemed trivial at the time.

In 1979 UNESCO designated La Antigua as a World Cultural Heritage Site. For the first time, a codified list of do’s and don’ts outlined what renovations could and couldn’t be made and what materials must be used. The neon signs and billboards were removed and overhead wires put underground.

Prosperity didn’t reach everyone. A Civil War, begun in the early 1960s, lasted 36 years. According to historian Elizabeth Bell, tourism in Antigua dropped to almost nothing during this time, and, of course, prosperity lowered for all but a few.

After the Peace Accords were signed in l996, non-profit organizations (NGOs) arrived from all over the world to help Guatemala get back on its feet.

Parque Central was an eyesore after the war according to people who saw it then. Maintenance had been put off for years. The cement benches were cracked and crumbling, and the shaft of the fountain was rusted and broken once more. No water had flowed for eight years. Fallen trees were a hazard and there was dangerous barbed wire which fenced off unsafe areas. Plus only one street lamp worked.

The Spanish schools, which started in the late 60s and 70s, were beginning to come back. Tourists were returning. The city fathers wanted to spruce the city up, and Parque Central was its heart.

Nuestros Ahijados (God’s Children) a local NGO, took on the renovation. Patrick Atkinson, its CEO, had the help and support from the Guatemalan Corps of Engineers and the Mayor of Antigua.

Mr. Atkinson used his own staff of gardeners (some blind) and the older children to dig out approximately 10 inches of topsoil. They had to remove the rubble beneath it, consisting of cement and tile, because the tree roots couldn’t get through and reach the water table.

The topsoil was replaced and wrought-iron green fences put around the planting areas. The fences had little sticks between the chain links to discourage children from swinging on them. They didn’t hurt, but were uncomfortable, also decorative.

Long cement benches—chipped and stained with urine and graffiti—were replaced with smaller ones with wooden slats and green ironwork like the fences. After 2½ years of work, the latest renovation of the park was finished in 2002.

Antigua has survived by serendipity and the tenacity of people who simply refused to abandon a lovely site. Its history reminds me of the story the Phoenix, a mythical bird of antiquity.