The Evolution of the Tortilla

text and photos by Louise Wisechild.

The savory tortilla, made from ground maize (corn), is Guatemala’s favorite food staple. Maize itself plays an important cultural and spiritual role in Mayan cosmology. In the Maya creation story, people were fashioned from yellow and white maize. Maize is the foundation of the Mayan diet and culture. Maize is also one of the most important gifts to the world from the Maya.

Though the exact botanical ancestry of maize is still debated, its domestication 10,000 years ago in southern Mexico is regarded as the greatest accomplishment in agricultural history. Whether maize originated with the tough-shelled seeds from the scrawny teosinte bush or was crossbred with grasses, it was the Maya who planted, tended and selected the best seeds from their harvests for the next year’s crop, over thousands of years.

As we walked through the field Chema selected tousled ears

and handed them to his two eager granddaughters

Maize is one of the few plants that does not reseed itself; it requires humans to plant it. Small ears of maize have been found in early Mayan sites, midgets compared to the voluptuous ears grown today. The Maya also understood that maize must be cooked with lime to unlock the plant’s nutritional value. Maize is now the third most popular plant in the world and supplies 20 percent of the world’s calories.

Today in Guatemala, Maya families continue to tend maize, often on the steep sides of mountains. For a season I followed Chema Gonzalez and his family through the life cycle of maize. Don Chema’s milpa, on the unpopulated side of Volcán San Pedro, is traditionally planted in late February using the seeds he saved from last year’s crop.

The land had already been cleared by fire. The vacant earth mimicked Volcán San Pedro in its succession of small pointed mounds, where last year’s maize had been planted. Chema knelt and took a handful of dirt to show me that the soil was moist even though it had not rained recently.

“Here we plant so that three stalks of maize will grow together and give more stability to the plants and a higher yield.”

After making a hole at the top of a mound, he deposited three kernels from the bag he had tied around his waist and then covered them with soil. Squash and beans, which are inter-planted in the lowlands, are not suitable for the mountains, Chema said. “Here we plant so that three stalks of maize will grow together and give more stability to the plants and a higher yield.”

By early May the leaves brushed my waist as I walked through the rows of vividly green, healthy plants. Chema’s daughter and granddaughter selected leaves from the corn for tamales and gathered edible wild greens that had sprung up between the stalks.

By the end of August, the plants towered high over my head, the thick close stalks like slender trees studded with multiple ears of maize. As we walked through the field Chema selected tousled ears and handed them to his two eager granddaughters, who cheerfully delivered them to the baskets of their aunts.

At home, the elote will be roasted and slathered with mayonnaise and Parmesan cheese.

The majority of the crop was left to dry on the stalk until January. I stood with the women as towering sacks of just-harvested maize began arriving on the bent backs of men wearing sombreros. The women smiled at the brimming sacks even though this would require several weeks of intensive labor to process. “Yes, we are very happy today,” they told me, “because there is enough maize for the entire year.”

The women began at once, tearing down the husks and cracking them away from the cob. The well-formed husks were tossed to a pile to wrap chuchitos, while the others would be fed to the horses.

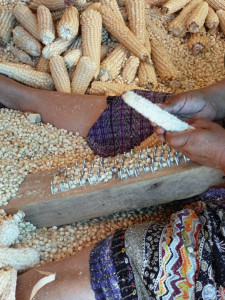

When all the corn had been husked, the process of degranulation, removing each kernel of maize from the cob, began. The women used a simple tool or even a screwdriver to remove each kernel; the bare cobs were tossed into a pile for animal feed and cooking fires.

The kernels were carefully collected—not one was left to be trampled in the dust. Next they were spread onto plastic tarps where they would be raked until thoroughly dry and ready for storage. The best ears were once again kept aside for next year’s seed, a precious genetic heritage saved to provide food for the future.

The women will soak the dried maize with lime water and then take it to a molindor to be ground, the only machine in the life of the maize. At home they will press the masa (dough) into their palms and clap it softly as it passes between their hands and emerges as a perfectly round tortilla.

Louise, your understanding of Maya culture continues to delight me, while it also instructs. The photos are excellent, too, especially the last one. I look forward to more articles by you.

Fascinating and clearly written with great photos. Thanks, Louise, for the info and images.