Saintly Beginnings

Monuments of Santo Hermano Pedro are rare on Tenerife, but there are several in La Antigua: (left) at the entrance to town, (center) in the garden of San Francisco Church, outside of the tomb where his remains lie, (right) at El Calvario Church where he first lived in Guatemala

Where did Hermano Pedro come from?

Young Pedro de Betancur, age 22, left his home on the Canary Island of Tenerife in 1649 and sailed to the New World. Many ships were crossing the Atlantic at that time, with Tenerife a geographically necessary port of call between Europe and America. They were filled with adventurers lured by the promise of gold and silver in abundance. Not Pedro. Humble and devout, he was inspired to join evangelizing efforts. It seems safe to assume that he really didn’t know what he would face.

For those who like to read the end of the story first, here it is. Pedro became Hermano Pedro and then Santo Hermano Pedro, the first saint of Central America as well as the Canaries. Pope John Paul II canonized him in Guatemala City in July 2002. Backing up briefly, the young Pedro landed first in Cuba, then Honduras. From there he walked, arriving in 1651, after two years of travel, in Santiago de los Caballeros, the Spanish seat of the government at that time, now La Antigua Guatemala. He held neither title nor prestigious connections nor do we know of anything else he had to offer—except his compassion and devotion. In his zeal for the priesthood he entered the Jesuit school in Santiago but just couldn’t make the grade. Pedro was accepted into the Third Order of the Franciscans and worked at the Church of El Calvario. In his off-hours he focused on caring for the poor, the sick, the homeless, the uneducated. He took ‘justice for all’ seriously.

Pedro declared, “Here I have lived and here I will die.” And so he did in 1667, his remains now lying in La Antigua’s Church of San Francisco. But when the young man thought of home, what did he think about? Now for the rest of the story.

Tenerife was formed by a volcanic eruption. Pedro was born in the peaceful and pastoral town of Vilaflor on the slope not far from a still active volcano. Just as in Santiago, he was probably familiar with occasional volcanic rumbles. And with a climate not unlike that of Guatemala, bright bouganvilla thrive on Tenerife, just as they do here.

Pedro was a poor boy.

He was a shepherd, tending a small flock in a place called Granadilla, a little down from Vilaflor, toward the sea on the southwest of the island. He helped his struggling family with four brothers and sisters. It must have been of some comfort to him to have landed in a place remarkably similar to his homeland.

More than five centuries ago today’s capital town of Santa Cruz of Tenerife was born and developed around its port. Although traces of the town’s origins remain, Tenerife’s real history is in the original capital of San Cristóbal de La Laguna, high up on the hill and safely away from pirate activity on the seas at that time. The urban design of San Cristóbal de La Laguna modeled that of many cities founded in the Americas by Spanish colonists, including Santiago de los Caballeros. The Franciscan church and monastery there were built in the late 1400s, over 100 years before young Pedro left home. The town is now the ecclesiastical and university center, but being at the northeast end of the island, it is not known whether Pedro was ever there.

Today in Santa Cruz, with a bustling commercial seaport, intense traffic of cruise ships and several good beaches, tourist business is booming. A recent law allows construction of only five-star-and-above hotels. Apartment buildings as high as 15 stories fill the town, painted in soft colors like the colonial shades of La Antigua. San Cristóbal de La Laguna, a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage city, is a 30-minute winding ride up the hill by a sleek, modern tram. The two towns make up the most populous area of the island, with a total of almost 400,000. It is difficult to tell where one ends and the other begins.

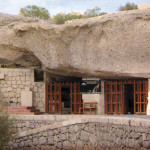

On Tenerife, Hermano Pedro’s history is told very briefly. Among the little left of those beginnings are his natal home and a cave that has become a popular pilgrimage site. The house has been reconstructed and now includes a church and convent of the Bethlemites, the women’s Order formed in Santiago by his followers. The cave is where the boy hid himself and his flock from harm at the hands of English pirates and African Moors who had been known to snatch youngsters like him and carry them away as slaves. Although the process toward canonization began in 1698, collecting information about his life, little is known that can be verified of the young Pedro.

The rest of the story is well-known in La Antigua, where the name and work of the fine young man from Tenerife live on. Just one example is Las Obras Sociales del Santo Hermano Pedro, home to almost 300 persons with severe challenges and where every year 270,000 patients of limited resources receive medical attention. ‘The Obras,’ as it is known, also has facilities to care for children and senior citizens and provide addiction rehab. Friends and relatives on Tenerife who knew Pedro the boy may never have had opportunity to know about Pedro the saint.

Curiously, while Pedro simply carried out kindness and acted justly in Guatemala, John Milton in England wrestled with causes and consequences of good and evil. Milton went blind in 1652, just after Pedro arrived in Santiago and before dictating his 10-volume Paradise Lost to his daughters. It was published in 1667, the year Hermano Pedro died.

photos: Jack Houston

- Las Obras Sociales del Santo Hermano Pedro, La Antigua, carries his name and continues his work. Currently it is home to almost 300 persons with severe challenges and where every year 270,000 patients of limited resources receive medical attention.

- The cave near Granadilla, Tenerife, where the boy hid himself and his flock from harm at the hands of English pirates and African Moors who had been known to snatch youngsters like him and carry them away as slaves. (photo: Juan Francisco D. Gómez)

- Sign on house off plaza of Belén Church, La Antigua, identifies a home of Hermano Pedro.

- Courtyard of municipal building in San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Tenerife, resembles colonial structures in La Antigua Guatemala.

Thank you for the story.

Statues of Hermano Pedro are not rare on Tenerife. There are those in Vilaflor, La Laguna, Granadilla, Arona, outside the Tenerifw South airport, etc.