Paradise in the Clouds of Quiché

The Cerro Amay Cloud Forest

by Philip D. Tanimoto, Ph.D.

One hundred kilometers north of La Antigua Guatemala, away from the noise and traffic of city life, in the department of Quiché, there is a remote mountain called Cerro Amay that is covered with a dripping, virgin cloud forest. With an abundance of wild resplendent Quetzals, two species of endangered monkeys and thousands of limestone caves, how is it that you’ve never heard of it before?

The story began 6 million years ago. The North American Tectonic Plate, one of several major plates in the Earth’s crust, was impacted by the north-moving Cocos Plate of the tropics, causing an endless series of earthquakes that lifted the limestone sea floor skyward, and at the same time, united South America with North America, resulting in the creation of Central America. With each successive quake, the mountain was pushed higher and higher, until it reached the clouds—over 2,600 meters (8,530 feet) above sea level.

The story began 6 million years ago. The North American Tectonic Plate, one of several major plates in the Earth’s crust, was impacted by the north-moving Cocos Plate of the tropics, causing an endless series of earthquakes that lifted the limestone sea floor skyward, and at the same time, united South America with North America, resulting in the creation of Central America. With each successive quake, the mountain was pushed higher and higher, until it reached the clouds—over 2,600 meters (8,530 feet) above sea level.

Once in the cloud zone, abundant mountain rainfall combined with tannic acid from fallen leaves to dissolve the limestone bedrock, creating thousands of unexplored caves. Earthquakes continue today at Cerro Amay, further fracturing the limestone, preventing the formation of lakes. Even streams are rare.

Think of a steaming tropical rainforest, and then cool the temperature way down into the comfort zone. Cover the massive trees with dense layers of moss, bromeliads and ferns. Replace the widespread lowland fauna like jaguars and toucans with species unique to the highlands, such as the resplendent quetzal, emerald toucanet, and the ubiquitous, bubbly songster, the gray-breasted wood-wren. To this, add the haunting yet stately tree ferns. Then bathe all the trees in an enveloping bank of dense clouds that soaks the forest and starts it dripping, even without rain.

This forest is technically called “tropical montane cloud forest.” Although it occurs around the world on tropical mountains, it is rare, comprising less than 2 percent of all forests, and much of it has already been destroyed by humans. But where it survives, it is a crucible for evolution, and species new to science are continually being discovered.

We have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to alter the trajectory of deforestation in Guatemala and to leave something pure and good for future generations of Guatemalans and foreign visitors.

As an ecologist conducting my doctoral research on one of Guatemala’s most iconic birds, the horned guan, I became involved with this mountain paradise in 2005 while analyzing satellite imagery to locate potential horned guan habitat. As a Pleistocene relic only distantly related to others species in the American tropics, the horned guan lives only in the isolated cloud forests of northern Central America and is classified as endangered due to the disappearance of its cloud forest habitat. The bird and the forest evolved together. Poring over the imagery, I stumbled upon what looked like a spectacular habitat where the horned guan might survive. Using the Internet, I discovered the name of this place, Cerro Amay, but I could find nothing else about it. Querying academic databases, I couldn’t find any research papers about the people, wildlife or natural resources of Cerro Amay, so I endeavored to visit this place on my own.

In 2007, I arranged with the Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (CONAP—the Guatemalan Protected Areas Council) to visit Cerro Amay. After extensive communications via email, they located indigenous guides to help me survey the forest for the horned guan, and the search began by climbing steep, slippery trails through the towering forest, often choked with bamboo thickets and blocked by limestone cliffs and sinkholes. Everything was cool, moist and incredibly green. Wild orchids draped the tree trunks. The territorial calls of endangered black howler monkeys reverberated through the forest, and soon, we saw them in the towering treetops while brilliant garnet-throated hummingbirds zipped past us.

At night, we camped in the wilderness under a plastic tarp to stay dry, and in the night, listened to the calls of animals such as the cacomistle, a distant relative of the raccoon, and a puma, or mountain lion, that was screaming nearby. We woke to the dipping and flutey mating call of the male resplendent quetzal, and the crystalline, descending call of the guardabarranca—the brown-backed nightingale thrush. To me, it was clear that before my eyes was a world-class ecosystem that had gone completely unrecognized by any scientific or governmental body. Each day this treasure survived intact was a near miracle, and if not protected, this enchanted forest would disappear forever.

On our way in, at the edge of the forest, we encountered a fresh road being bulldozed across a steep escarpment, without care to the environment, leaving a muddy, eroding mess behind it. We worked our way sadly past the noisy machine and its operator. In the years that followed, the greater threat to the ecosystem that this road posed would be realized. But for now, finding this undiscovered paradise was a remarkable event that swept my life in a new direction. For the wildlife that lived here; for the ecological services provided by a pristine ecosystem; and for the enjoyment of future visitors, I decided to try to secure the complete preservation of Cerro Amay—to make it into a permanent nature preserve.

In the seven years since then, my colleague, Elias Barrera, and I have done everything we can think of to try to protect Cerro Amay. With few resources, we have been spreading the word about this special place. We have talked with government officials and worked with local communities to try to stop illegal logging. We have been implementing sustainable development projects to stimulate new economic activity in poor, indigenous villages.

We have made presentations to international conservation organizations, and we have been writing grant proposals to international foundations to promote and protect this place. Over the last year, we have implemented a set of automatic trail cameras that have been capturing a spectrum of wildlife photographs, including the secretive brocket deer and the margay—a little-known spotted cat. We are also engaging with outside scientists, who are coming to Cerro Amay to survey the amphibians, insects and birds. This year, one of these entomologists found two beetle species new to science.

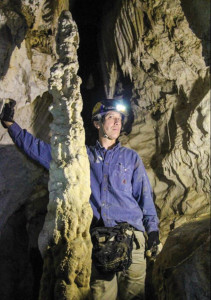

Last March, we established a new eco-tourism program. Over the course of several days, the very first tourists experienced the wonder of the cloud forest wilderness. Seven hardy adventurers from the U.S., each with a vision and a passion for the future of the world, came to learn and experience the cloud forest. They rappelled into the depths of newly discovered Dragon Cave to see a plethora of beautiful limestone formations.

They ascended into towering oak trees where they tied in safely and relaxed as they gazed out across the magnificent forest while listening to the calls of howler monkeys in the distance. From our Maya guides, they learned about ethnobotany—the use of medicinal and edible forest plants, and afterward, experienced the local hospitality of the highland Maya, including the rejuvenating treatment of the temescal, or Mayan sauna.

Everyone came away with a deep appreciation for the combination of geologic time and isolation that allowed the biodiversity of Cerro Amay to evolve. The trip was so successful that we are planning another trip in 2016.

Despite our progress, this cloud forest is still severely threatened. Illegally cut logs are being trucked out along the poor dirt road we watched being carved into the mountain, and chainsaws can be heard cutting down the cloud forest. Cerro Amay lacks any overarching legal protection, and each year, more forest is cleared to make agricultural fields—fields that will be laboriously worked by poor farmers, and coaxed into producing only a meager harvest of unending poverty.

So the challenge remains. How in Guatemala can we create a new natural preserve that mimics the Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve in Costa Rica, which brings in thousands of tourists from around the world and millions of dollars of income, while simultaneously protecting the forest? There is no blueprint for this process, yet we remain optimistic. We are gaining visibility.

We are bringing in new biologists and new eco-tourists, and we are establishing working, trustful relationships with the indigenous communities around Cerro Amay while helping them to achieve many of their own goals through new, high-value specialty crops. We envision a slow groundswell of increasing public participation and ecological awareness, combined with sustainable development and the kind of investment opportunity that has helped lift other areas out of poverty.

One thing is certain. We have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to alter the trajectory of deforestation in Guatemala and to leave something pure and good for future generations of Guatemalans and foreign visitors.

Our next tour of the Guatemalan Highlands, cloud forest wilderness, and indigenous villages is scheduled for the end of February and early March, 2016. Tours are currently organized by Inchanted Journeys, with whom we cooperate closely.

Click here for more information. Depending on the number of inquiries we receive, we may schedule additional tours for 2016. Group size is held to a maximum of 10 clients plus our gringo and indigenous guides. We hope to hear from you! Visit The Cloud Forest Conservation Initiative website.

It’s official! Our next eco-trek in the Guatemalan highlands and Cerro Amay will be 06-22 March. Join us, or contact us!

A fascinating article. Wath a trip. Y pensar que en Guatemala existe esta clase de paraiso y no lo sabemos. Y muchos otros más. talvez sea mejor, si no ya lo hubiéremos destruido. Felicitiaciones Review Magazine. I love you.

Thanks so much for the kind words Italo. We love promoting the best of Guatemala.

I think Sandra Moran, newly elected to the Guatemala Congress for the Convergencia party, would support this cause. Her background is mainly in poverty issues and human rights but she’d surely want to help you with this plan. Maybe it could be made into an Avaaz campaign (?)

Thank you so much for commitment.

With much appreciation, Sheila