Mystery at Tak’alik Ab’aj

The proud team of excavators of the Tak’alik Ab’aj National Project who discovered Monuments 215 (in front) and 217

“Standing Stones” site yields unprecedented sculpture

Archaeologists recently discovered ancient altars, monuments and an unprecedented stone sculpture at a 2.5-square-mile Mayan ruin near Retalhuleu in southwestern Guatemala.

Representing both Olmec and Maya cultures, the Tak’alik Ab’aj (Standing Stones) site was inhabited for nearly 1,700 years, starting roughly in 1000 BC, and was a key trading center with ancient merchants traveling from present-day El Salvador and Mexico. Since excavations began in the late 1800s, more than 250 buildings and monuments have been uncovered.

Archaeologists Christa Schieber de Lavarreda and Miguel Orrego Corzo, from the Guatemala Ministry of Culture and Sports, have in recent years been leading an excavation that has produced a stream of important discoveries, including evidence of one of the earliest royal burials ever found in an important Mayan site. In March 2008, the team unearthed Altar 48, the monument to the birth of Mayan culture. In June and August, additional monuments (215 and 217) were discovered.

Because so many archaeological sites are yet to be excavated and studied, it is predicted that the established concepts about Mayan history will change substantially over the next 20 years.

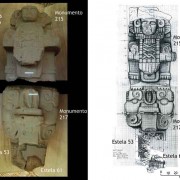

“Reconstructing” with photographs and carefully executed drawings of the imposing character (Monument 215) standing on top of the monster bat “capital” of the column-sculpture (Monument 217). The fragments of Stele 53 and 61 fitted with the remains of the column, thus recovering more of the ancient texts at its sides. All together it makes a monumental column-sculpture of at least 2.30m in height, and in every sense a historic landmark at the ancient city Tak’alik Ab’aj.

At a recent press conference, de Lavarreda and Orrego said the mysterious, enigmatic sculpture, known as “The Carrier of the Ancestor of Tak’alik Ab’aj,” is an unprecedented find. The sculpture presents an imposing character, decorated with insignias of power with certain Olmec characteristics. “The monument is unique and represents a great challenge for archaeologists,” de Lavarreda and Orrego said.

“Something very surprising is that this character is carrying a small human figure on his back. This small human figure has the position of his arms on his chest and hands folded down, and very straight legs, similar to those infants who are often found in the lap of the Olmec jade figures. These infant figures have been interpreted by some archaeologists as divine beings or ancestors. The quality of the volume and complete form of the sculpture conveys the formal concepts of Olmec art sculpture; however, this sculpture seems strange,” they reported.

The small human figure—is it the representation of the ancestor?—carried at the back of the personage of Monument 215.

“It is important to note that the small figure on the back of the standing character is literally joined by an extended cloth or skirt to the head of the bat. It is evident that the intention of the sculptor of this figure was to communicate the importance of the union of the carrier of the ancestor with the monster bat.”

Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego said this sculpture raises many questions:

- Why is the character carrying a small figure on his back?

- Who is the character and who is the little creature?

- Why is this character standing on a bat?

- Why is the sculptural style of the character different than that of the bat?

- What message did the sculpture transmit?

- Why was this sculpture destroyed and its pieces then included in the structure of the wall?

- Where had this sculpture been standing so it could be seen from all four sides?

The imposing character of Monument 215, the alter having been lifted carefully by the crew into upright position

The archaeologists said it could have been carved at or just before the start of the early Mayan era, in the transition of Tak’alik Ab’aj from the Olmec era to the Mayan era.

“Could it be that the early Mayan sculptor wanted to invoke the preceding Olmec culture as ancestors, as it later appears in the Mayan steles, where the ancestors are depicted watching from the heavens to protect and legitimize the power of the ruler represented below?” de Lavarreda and Orrego asked.

The monster bat head lifted into upright position. On the top of the head are the remains of the feet of the personage of Monument 215, which originally had been standing on the “capital” of monster bat head of the column-sculpture.

“We think that this is actually good news,” de Lavarreda and Orrego said. “In the past looting and ransacking of unprotected archaeological sites in remote areas presented a serious problem, a heavy loss to the cultural heritage of Guatemala. Maybe now, with more responsible archaeological institutions and a new perspective of archaeology, the undiscovered sites present a unique opportunity to preserve the cultural heritage of Guatemala and make new exiting discoveries about the ancient Mayas and their mysteries.”

With the collaboration of Barbara Schieber/Editor, The Guatemala Times, this article is based on New Maya Olmec Archeological Find in Guatemala published in October 2008 on www.guatemala-times.com and the authorization by Christa Schieber de Lavarreda and Miguel Orrego Corzo, Ministry of Culture and Sports, Head Office of Cultural and Natural Heritage, Tak’alik Ab’aj National Project, NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARK TAK’ALIK AB’AJ El Asintal, Retalhuleu, Guatemala.

Editor note: In the mid-1960s, a North American archaeologist named this site Ab’aj Tak’alik, using Spanish word order—but grammatically incorrect in Quiché. Several years ago the Ministry of Culture and Sports officially switched the order of the words to Tak’alik Ab’aj, which in Quiché means “Standing Stones.”

Pingback: GuateFriends Top 5 Favorite Places to Visit in Guatemala! - Guatemala Hostal Blog