Mayan Royal Tomb Unearthed

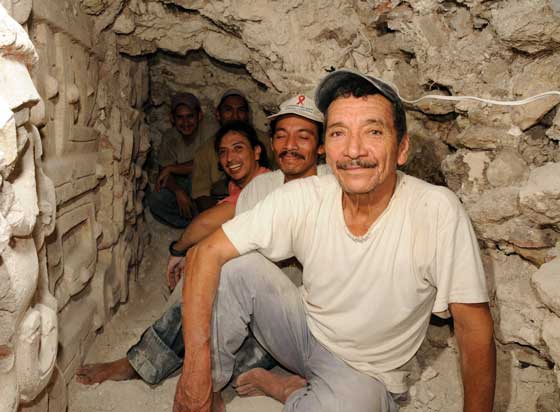

Front to back: Don Humberto «El Diablo» Amador, followed by his son Jenry, Lic. Edwin Román and Eliceo and Donis Alvarado. El Diablo, El Zotz, Petén. (photo by Arturo Godoy)

In the dense jungle of Guatemala, in the Petén Basin region which is home to the ancient Mayan city of Tikal, looming pyramids, looted tombs and overgrown paths that once served as Mayan superhighways speak of an era of ancient kingdoms and powerful warring dynasties. It’s easy to die and be forgotten here for thousands of years amid the thick vines, monsoonal rains and teeming vegetation that over time buries temples, jade, textiles, bones — both human and animal — only to resurface again, sometimes 1,600 years later in a place called El Diablo, the devil.

El Diablo — named for the steep climb that feels like punishment from the devil himself — is a pyramid on the outskirts of El Zotz, around 23 kilometers west of Tikal, from where Edwin Román Ramírez, 32, Guatemalan archaeologist and co-director for the bi-national Archaeological Project El Zotz, can stand atop the steep slope and see the pyramids of Tikal in the distance.

“The trek we make every year into the jungle helps us to understand the landscape and how close these two archaeological sites were throughout history. But they were not friends,” Román tells me from an undisclosed city in Guatemala where all the artifacts from the project are stored and classified under constant fears of theft and looting.

The El Zotz Project started in 2006, first mapping and then digging on the periphery of a powerful city like Tikal to determine what happens while living under those conditions. “What we think is going on after some study of the hieroglyphs is that this is some kind of buffer state. It was a kingdom that was

between other more powerful dynasties and elected to ally itself with the enemies of Tikal as far as we can tell,” said project director Stephen Houston, who teaches at Brown University, the institution financing this collaborative project. This year brought in the biggest team yet with 80 to 90 laborers and at least 20 archaeologists — half Guatemalan and half foreigners as legally stipulated for bi-national projects — into the remote jungle for some three months.

They didn’t get far into their season when they made their greatest discovery: a burial chamber that they believe is the tomb of King Chak’ Ahk, one of the first kings of a Mayan dynasty to settle in El Zotz. The tomb was found on May 28 at the base of El Diablo where they, particularly Román, had been tunneling this pyramid, which was 40 percent collapsed and looked like Swiss cheese because of all the looting. The tomb was about nine feet deep and four and half feet high and sealed with alternating layers of mud and rock, which helped keep it airtight for well over 1,600 years.

The process of finding the tomb involved first discovering the elaborate stucco masks that had been painted red and then digging through a looter’s tunnel, which the team began to clean out. “Working in tunnels is one of the most dangerous jobs that exists. You can only see the width of the tunnel, in this case one meter, everything else is your imagination,” Román said.

Once inside they found a small building in front of this great temple which had effigies of what appeared to be the Sun God and then a smaller enclosed building which, through digging deeper, they soon discovered had caches of vessels or ceramics that contained human body parts as a sacrificial or ritual offering.

“Under that we began to uncover row after row, layer after layer of stones, and it did seem to have increasingly the feeling of a bank vault, almost as if someone had been concerned about security in this fairly unstable political zone and for the protection of whatever lay underneath,” Houston said.

One after the other, they discovered more of these caches containing body parts, fingers, often surrounded by areas of red that probably corresponded to the decayed flesh of the fingers themselves. There were teeth. In one of the vessels they found an incinerated, partly cremated baby.

“There was a lot of misery that went into encasing this tomb’s magical and protective circuit,” Houston said.

After a week or so of this very labor-intensive archaeology they reached the same level as the base of the tomb.

They carefully shaved away at the wall and slowly lowered a light bulb into the tomb. Suddenly, there was a pinprick of light reflecting inches, if not centimeters or millimeters, from the tomb itself.

“When I started going down it was spectacular to see all dark, dark, dark, and then when the light bulb was lowered all the light that projected those colors below — green, pink, red, black, brown. Then to see this chamber was spectacular,” said Román, carefully brushing sand off one of the pots found in the tomb.

I found him and Sarah Newman who was working with Román on the tomb site, in the afterglow of their find, cleaning up artifacts in a laboratory that resembled a dorm-room setting.

They would then carry all these artifacts to a small, windowless room, which had shelves up to the ceiling filled with labeled plastic bags containing more artifacts.

“My first thought was, ‘Oh my God!’” Newman said, almost giggling, joking that it was downhill from here in her professional career. “My second thought was, ‘What are we going to do with all of this?’ There were many things that as archaeologists we just don’t know how to deal with.”

When they opened up the tomb there was the chill of almost semi-refrigeration as if the layers of riverbed, swamp mud and stone had served to protect the tomb. Once they opened it the rotting began again and both Houston and Román remembered a distinctive rotting smell of putrefication inside. Time had been suspended for 1,600 years until now. There was an urgency to things now.

“Royal tombs are found very seldom in any part of the world. So that when the tomb of the pharaohs is discovered it’s something that revolutionizes Egyptology… A royal tomb is a quantum leap beyond any kind of grave,” said Houston.

It also sets a milestone for the recent field of archaeology in Guatemala, which dates back 30 years to Juan Pedro Laporte, who created the field at the School of History at Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (USAC); he passed away this year. There are now around 140 graduates in the field of archaeology from both Universidad del Valle and USAC.

Finding the tomb also has a personal significance for Román — a way of doing politics in his life that involves working and studying his ancestors and “studying the past in order to give it to fellow Guatemalans and say, ‘Look how great our past was, imagine what our future can be if we work together.’ For that reason I will always come back to Guatemala, to share what little I know with the younger generation.”

Photos by Arturo Godoy

- Front to back: Don Humberto «El Diablo» Amador, followed by his son Jenry, Lic. Edwin Román and Eliceo and Donis Alvarado. El Diablo, El Zotz, Petén.

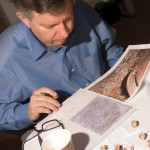

- Dr. Stephen Houston examines photographs and artifacts from the Royal Tomb.

- Fragmented vessel nicknamed Dragon Head

- Sarah Newman (Brown University graduate student) and Lic. Edwin Román, Guatemalan Co-director of the El Zotz Project, having their lunch break just outside the tunnel leading to the stucco masks and the Royal Tomb. El Diablo, El Zotz, Petén.

- Head on a lidded fragmented vessel.

- One of the very first pictures of the Royal Tomb, taken through an approximately 15 x 20 cm hole. El Diablo, El Zotz, Petén.

- Laboratory analysis of bones

- Illustrating shards

- Lic. Edwin Román and Ewa Czapiewska (graduate student at University College London and the ceramist of the project) assisting Dr. Stephen Houston. El Diablo, El Zotz, Petén.

- Sarah Newman drawing excavation profiles. El Diablo, El Zotz, Petén.

- Fragmented lid of a vessel, with the head and painting of a peccary.

- One of the stucco masks found in the substructure of the pyramid. El Diablo, El Zotz, Petén.

- Drawing of a turtle on a vessel lid.

- Composite image of the roof of the Royal Tomb. El Diablo, El Zotz, Petén.

- One of the lids from the 32 vessels found in the Royal Tomb. El Diablo, El Zotz, Petén.

Pingback: Dr. Jones Got Nothing on Us – [Scenes from the Petén Jungle] | Albatrosdelmundo's Weblog