José Cecilio del Valle of Guatemala

On the eve of celebrating Central America’s independence from Spain, and six years before its 200th anniversary, a Guatemalan remembers José Cecilio del Valle, his long-forgotten great-great-great grandfather, a key player in the region’s independence and one of the great thinkers of his time. (1780-1834)

Mexico and Central America became independent from Spain on Sept. 15, 1821, but it would take until 1823 before Mexico separated from Central America, which then disintegrated into separate republics. Honduras was the first to claim its independence. Guatemala followed.

Mexico and Central America became independent from Spain on Sept. 15, 1821, but it would take until 1823 before Mexico separated from Central America, which then disintegrated into separate republics. Honduras was the first to claim its independence. Guatemala followed.

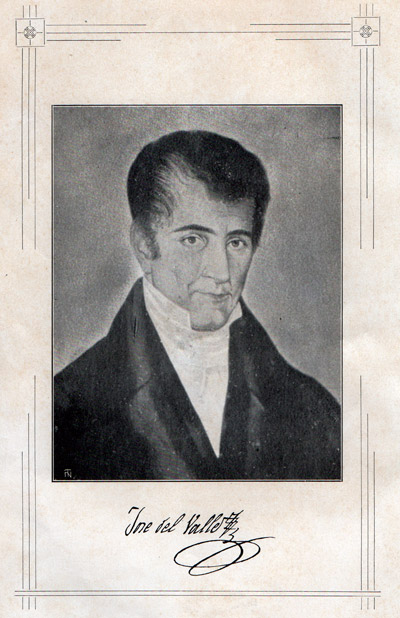

José Cecilio del Valle was born a creole on Nov. 22, 1780 to a wealthy Spanish family in Choluteca, Honduras. His family moved to Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala (present-day La Antigua Guatemala) when he was 9 years old so he could have access to a better education. At that time it was the capitanía or capital of Central America, a colony of Spain.

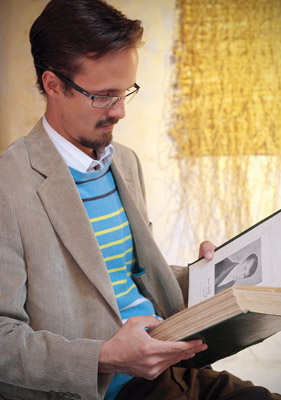

Bernardo del Valle Pedroso, marketing manager at La Antigua Guatemala’s Mesón Panza Verde, is the fifth of five generations of Bernardos, who began with his great-great-great grandfather’s son.

Guatemalan history took on a special significance for young Bernardo at age 7, when his grandfather, Dr. Bernardo del Valle, founder of the Instituto de Cancerología (serving low-income cancer patients), sat him down to tell him about their family history.

“I want to tell you where your name comes from,” said Dr. del Valle, in his 80s at the time. Young Bernardo or Nayo (his nickname), was intrigued. “You, your father and I are not the only Bernardos in the family; you are the fifth Bernardo named after José Cecilio del Valle’s first son, José Bernardo. José Cecilio del Valle wrote the [Central American] Independence Act.”

The personalized history lesson developed in installments over the years, but the seed was planted that day: José Cecilio del Valle was no longer an abstract character whose life he had to memorize and regurgitate when tested on the subject in school. Instead, this great man jumped out from the history pages and came to life.

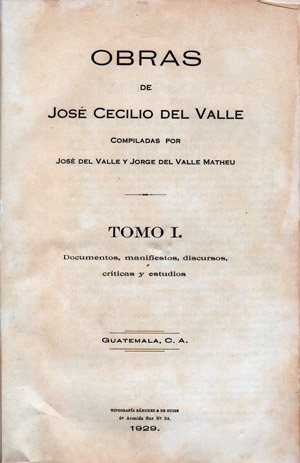

Seven years later, when Nayo was 14, he had a school assignment on Guatemala’s independence and asked his grandfather for help. His response surprised him: It came in the form of a loan, a book: “José Cecilio del Valle’s works (volume I),” compiled by relatives and printed in 1929.

The book led to another surprise once he opened it: the discovery that Guatemala has always celebrated its independence on Sept. 15, regarding it as mistakenly taking place in 1821. In the old volume with yellowed pages he could read that the year corresponded to the date when Central America and Mexico separated from Spain, and that the correct year for Guatemala to celebrate its independence is 1823, when Central America separated from Mexico and each Central American republic claimed its sovereignty.

“My first thoughts were, ‘Whoa! What happened here?’” he recalls. The discovery only made him want to learn more about, basically, how the whole country celebrates the wrong year of independence. Along that road of discovery, he also found plenty to be proud of too.

“I felt very proud of where I come from; José Cecilio del Valle abolished slavery [in Central America] even before U.S. President Abraham Lincoln did,” he says beaming. “He also wrote the Central American Republic’s act of independence, yet he never signed it … a republic that no longer exists but that achieved its independence from Spain with zero violence.” Knowing more about his great-great-great grandfather became an obsession.

In the years that followed, especially after his grandfather Dr. del Valle died, Nayo led a personal rebellion of sorts against formal education. Instead he channeled his energies into reading everything he could get his hands on regarding José Cecilio del Valle.

Then his mother gently steered him toward the library dedicated to his great-great-great grandfather at the Francisco Marroquín University, which included old letters he exchanged with European thinkers such as Alexander Von Humboldt, and a large collection of books he owned by J.J. Rousseau and Voltaire, among others.

His grandfather had donated everything to the library in 1986, the year Nayo was born. The collection included at least eight books penned by French philosopher Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle, due to whom del Valle Pedroso suspects that his great-great-great grandfather took a liking to the name Bernardo. Le Bovier de Fontenelle firmly believed that collective independence can only be achieved via individual independence. And thus Nayo found his mission.

Although it took him a few extra years to graduate from high school, it was learning about José Cecilio del Valle (a staunch believer in education) that inspired him to earn his high school diploma and move on to college. But something else happened: His great-great-great grandfather’s persona also seeped into almost every nook and cranny of his life.

Despite having been born to a family that owned 16,000 heads of cattle, José Cecilio del Valle’s biographers (and descendants) describe him as having lived a very austere life as he studied law, metaphysics and philosophy in the mid and late 1790s at the San Carlos University in La Antigua Guatemala, the third university founded in Latin America.

It is no surprise then that his great-great-great grandson Nayo would follow his illustrious ancestor in his pursuit of knowledge with similar austerity.

Nayo’s first job was sweeping and cleaning, then he was employed as a baker, followed by multiple odd jobs, to support himself while he studied. He also suffered the pains of becoming an experienced chef: getting one too many cuts on his hands.

Today Nayo lives in Antigua and walks half an hour to work every day. He has become a self-made man, despite coming from a privileged background. He is multilingual and has cultivated several disciplines, particularly in the arts: he is a professional chef, musician, designer, marketer and an entrepreneur.

Nayo is a walking tribute to his great-great-great grandfather who was also fluent in several languages because, according to his family biographers, he believed that learning foreign languages multiplies the soul’s perceptive aptitudes. “Hence his knowledge of Latin, English, French and Italian and his intimacy with the works of Cervantes, Newton, Cuvier and Dante, among others,” the biographers say.

Sixteen years after “José Cecilio del Valle’s works (volume I)” was placed in his hands, Nayo is determined to honor his great-great-great grandfather’s legacy to Central America and its independence. He has begun the work of organizing a collective effort to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Central America’s independence from Spain in 2021 by involving both private and public sectors to generate development and self-sufficiency for communities in need.

In his time, José Cecilio del Valle also found original means of channeling messages worth conveying. Despite his belief in spreading knowledge, one of his first jobs was as censor for the Spanish colony, a position that allowed him access to the latest works of European thinkers.

“The Spanish crown did not want these works to reach its colonies in America so quickly because it would mean that the crown could lose its power, and only allowed certain portions to be accessible to the public,” Nayo explains.

But his great-great-great grandfather found a loophole: journalism. He published the first Central American newspaper, “El Amigo de la Patria,” (The Nation’s Friend) and used it to print articles of watered-down versions of the censored European thinkers’ works.

Fast forward a couple of centuries, Nayo is following his footsteps with a slightly different take. Last year he created a Facebook page titled Independizarte to post his thoughts about the demonstrations leading up to President Otto Pérez Molina’s September 2015 resignation and incarceration on corruption charges.

To Nayo it was a means of digesting and spreading the meaning of empowered Guatemalans finally standing up collectively to authority after decades of silence, mirroring many of his generation who took to social media with a single language of unity among individuals, communities and countries in the region. According to him, it’s something his great-great-great grandfather would have applauded.

“That is why the celebration of Central America’s independence [in 2021] is an enterprise inspired in José Cecilio del Valle’s memory, because it’s thought of as a platform for regional unity,” he explains.

While it is still in the making, the guiding spirit is a collective production of different artistic expressions to deliver the message on the importance of independence. “If José Cecilio del Valle is present in anything here, it’s in the principle that nobody has the right to decide for other people,” he says.

According to Nayo, back in his day José Cecilio del Valle was more an independence adviser than a protagonist. His great-great-great grandfather believed that independence was a process, not a single event, an idea that was met with resistance because creoles were eager to rid themselves from the Spanish colony to seize the power themselves.

Although his stand did not stop the events that followed, and his popularity garnered him political enemies, some relatives suspect that José Cecilio del Valle was poisoned because he declined to sign the independence act from Spain that he himself had written, believing that the timing was not right, just yet.

“There are accounts that he had experienced a burning sensation in his chest before dying,” says his great-great-great grandson. “My aunt Rebeca Zabalza told me that he was poisoned with the root of a plant called camotillo, famously used back then to poison someone in small doses over a period of time.”

Almost eleven years after Guatemala had become a republic, on March 3, 1834, José Cecilio del Valle died in Mexico at age 54, oblivious to the fact that he had been elected president of Guatemala in absentia.

By then, it had become clear that independence from Spain and Mexico had not been fostered by a genuine desire for independence—the kind José Cecilio del Valle dreamed about. But Nayo hopes that looking back at Guatemalan history and his great-great-great grandfather’s role in it could help lead the way into this current-day process, a learning curve on how to build individual emancipation and a collective one in Guatemala and Central America.

REVUE article by Julie López