In the Highlands of Guatemala

In the Highlands of Guatemala, one Maya Community is taking back its Cultural Identity.

Innovative educational programs help the indigenous Poq’omchi’ of San Cristóbal Verapaz regain their voice after decades of oppression.

On a sultry afternoon in late June, dozens of men, women and children pour enthusiastically into the “Salon Esperanza” at a high school in San Cristóbal, a predominantly Poq’omchi’-speaking, Maya municipality in the cloud-forested Highlands of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala.

Most notable are the women with striking features and straight long black hair wearing their brilliantly colored traje, a traditional hand-woven Maya dress that has survived for centuries.

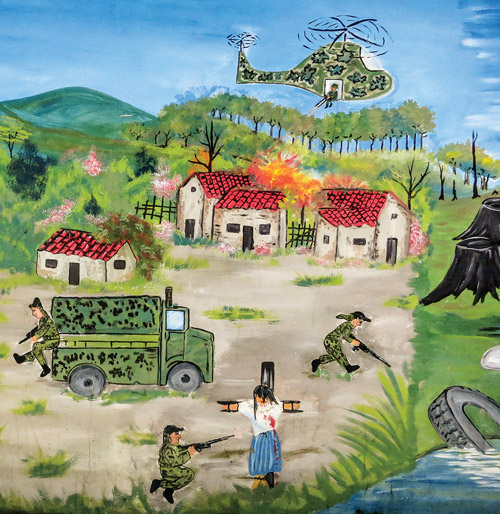

Woman and girl in San Cristóbal Verapaz walk in front of a mural depicting

a soldier from Military Zone 21 and the military’s scorched-earth

policy during Guatemala’s civil war.

mural by Oswaldo Lem Peréz / photo: Kerstin Sabene

Community members from all walks of life and entire families were gathered here to view the documentary “Benedicto,” featuring retired Gen. Manuel Benedicto Lucas García, who served as the Guatemalan army’s chief of staff under his brother’s military dictatorship from 1978 to 1982.

García is considered to be one of the masterminds behind the military’s scorched-earth campaign in the early 1980s, an operational strategy of punishment, displacement and annihilation of civilians.

In the film, he speaks to his role and responsibility as commander of the counterinsurgency during the war, and about Creompaz, the case for which he will now stand trial.

In Guatemala, June 21 commemorates a National Day of the Disappeared. The three-hour gathering and film presentation, titled “Foro Memoria Historica,” was one of many memorials held throughout the country during this week to honor those who disappeared and to help survivors to heal.

Clearly present on this day in San Cristóbal’s “Salón Esperanza” was a lingering pain still felt by families awaiting long-overdue justice for atrocities committed against loved ones.

No one understands this better than Humberto Morán Ical, a lifelong resident of San Cristóbal who lost two brothers during his country’s brutal civil war.

“One of my brothers was identified a few years ago by forensic scientists after they uncovered mass graves containing the human remains of 558 people at Creompaz,” he recounted. “A second brother disappeared from the nearby municipality of Tactic but he has never been accounted for.”

Last year, Morán Ical and about 25 other residents of San Cristóbal Verapaz participated in a creative educational project led by Dr. Ruud van Akkeren, an anthropologist, professor and ethno-historian who has been working closely with Maya communities, NGO officials and local educators for more than 20 years.

Having written extensively on ancient Maya culture, including numerous scholarly articles and books, Van Akkeren took a clear divergence from his traditional teaching approach and asked members of the San Cristóbal Verapaz community to collaborate and write the chapters of a new textbook themselves.

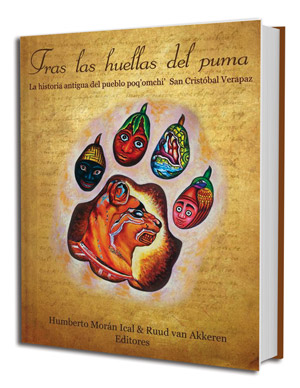

The book, titled “Tras las huellas del puma” (Following in the footsteps of the puma), explores the pre-Hispanic history of the Poq’omchi’-speaking people of San Cristóbal Verapaz. During colonial times, San Cristóbal was known as San Cristóbal Kaqkoj or “Puma” in the Poq’omchi’ language. The Kaqkoj or Puma, explained Van Akkeren, was the founding lineage of the town, hence the book’s namesake.

Working closely with Verdad y Vida, an NGO (non-governmental organization) based in Guatemala’s capital, Van Akkeren’s workshops and teaching methods aim to help surviving Maya who suffered during the internal conflict, to heal by recovering historical memory and reconstructing a connection to their ancestral past.

“Part of getting back their self-esteem is by getting to know their own roots,” said Van Akkeren. “The Poq’omchi’ have a strong cultural history but there is still a lot of knowledge at a local level that just hasn’t been organized yet.”

While the state of education in Guatemala has improved since the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996, education here is to a great extent largely underfunded. “Very little Maya history is even included in the Guatemala educational curriculum, especially as it concerns the Highlands,” said Van Akkeren. And with globalization comes a continuous struggle for the indigenous to maintain their identity and traditional way of life.

“It was an honor to contribute to the publication of ‘Tras las huellas del puma,’” said Morán Ical, who studied agriculture but has always had a passion for history and archaeology. “And what a great opportunity for me as well because I love to write, so I was able to combine my work with archaeology, visiting local Maya sites and learning from the experience.”

As we walked the shores of San Cristóbal’s shimmering blue Laguna Chichoj, Morán Ical, who served as co-editor of the book with Van Akkeren, shared his thoughts on why this undertaking is so important.

“It’s because the book now truly belongs to the people. More often than not, archaeologists and researchers come here and just take the information and then publish it, but their investigation is not returned to the people,” he lamented.

“One of the other things I did for this project,” he added, “was to document people’s oral stories and history as they remembered it. This is significant, as the older generation can’t write and we didn’t want to lose good stories just because they had never been written down before.”

It is not uncommon for Maya communities throughout Guatemala to view oral storytelling and narratives as authentic. Yet, through innovative educational programs such as those facilitated by Van Akkeren, many more indigenous communities are recognizing the value of written documentation to authenticate that history.

By conducting their own research, and uncovering historical evidence of places and mythologies from their ancestral past, the Poq’omchi’ of San Cristóbal are protecting their story, which at this moment is at risk of slowly being forgotten. According to Guatemala’s Academy of Maya Languages, there are about 114,000 Poq’omchi’-speaking people left in all of Guatemala.

“It’s important to know where we came from and who we are,” said Oswaldo Lem Pérez, a lifelong resident of San Cristóbal and an artist who was among the book’s 22 authors.

“I was very excited to learn about the origins of the Poq’omchi’ people and to be able to work with Ruud van Akkeren. He helped rescue and recapture our culture and for that we will be forever grateful.”

Lem Pérez lost three cousins during the war. “Two of my female cousins were captured and hauled off to prison, and then taken to a different location outside of town where they were assassinated,” he recounted. Tragically, this was not an uncommon occurrence in indigenous communities throughout Guatemala.

According to human rights groups, over 1,000 people vanished from and around Cobán, capital of Alta Verapaz, between 1980 and 1983. While this number includes those from its outlying communities such as San Cristóbal, it is only a smaller representation of the more than 40,000 − mostly indigenous Maya − who “disappeared” throughout Guatemala during the country’s 36 years of internal conflict. Over 200,000 people perished during the civil war.

It is impossible not to sense the presence of Oswaldo Lem Pérez when you walk through San Cristóbal, as many of its colorful street murals are his work. One, depicting a soldier from Military Zone 21 in Coban and the army’s scorched-earth policy, is especially poignant.

Today, this military base is known as Creompaz and it is used for U.N. peacekeeping missions. Lem Pérez’s artwork also graces the cover of “Tras las huellas del puma,” with its life-like puma illustration.

Woman walking past mural in San Cristóbal of puma and maguey plant. mural by Oswaldo Lem Peréz / photo: Kerstin Sabene

“The Poq’omchi’ culture is very special,” stated Sucely Ical Lem, director of the Katinamit Museum located in the heart of San Cristóbal Verapaz and a treasure trove of photographs, books and Poq’omchi’ artifacts, some dating back several centuries.

“It was a very positive experience for me to participate in this project,” she stated. “Not only does it strengthen our identity as a people, but it is especially important for our youth.”

In his capacity as a teacher, Van Akkeren has empowered San Cristóbal Verapaz residents to recapture their history lost during decades of increasingly oppressive social hierarchy and civil war. They in effect are the true authors of an illustrated textbook that will be useful for future generations and is an important contribution to Guatemalan culture and its educational institutions.

Van Akkeren recently concluded a workshop in the Poq’omchi’-speaking town of Santa Cruz, Alta Verapaz, a neighboring municipality of San Cristóbal Verapaz. The intensive, seven-week course, which will be repeated next year, examines, among other topics, the origin of the Poq’om or present-day Poq’omchi’ and Poq’omam people who share a common lineage and speak related languages.

Contrary to most accepted theories on the matter, Van Akkeren postulates that the Poq’om were the founders of Kaminal Juyu, a sprawling Maya archaeological complex located in and below Guatemala’s capital.

His workshops are open to all local residents, especially teachers, he emphasized. “This way they can inspire and pass on newly acquired knowledge of their ancestral roots to their own students and future generations to come.”

REVUE article by Kerstin Sabene

*A majority of Mayan linguists spell Poqomchi’, Poqomam, and Poqom without a glottal stop (apostrophe) after the letter q. Van Akkeren disagrees, which is why the spelling in this story reflects his preference.

Can’t wait to see the movie and read the book about this beautiful community in Alta Verapaz in its struggle to regain their voice and define their culture.

I wrote about this area in “Different Latitudes:My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond” although not with the expertise and knowledge Oswaldo Perez undoubtedly provides.