BOOK ALERT: Incidents in the Life of a Maya Archaeologist

Ed Shook approaches the reader of Incidents in the Life of a Maya Archaeologist “with outstretched arms and a toothy grin” and welcomes the unsuspecting into a life that, as he tells Winifred Veronda, didn’t progress from point A to point B but zigzagged from a night school engineering class to six decades as a Mayanist.

That journey included the excavation of Tikal and the restoration of the Santo Domingo Monastery in La Antigua Guatemala. The Sunday buffet at the Hotel Casa Santo Domingo is in the room that once housed Shook’s 3,000-volume library.

Shook describes himself as “bluffing” a bit in his willingness to take advantage of opportunities that suddenly presented themselves. In the midst of the Depression, with bread lines in American cities, Shook sat in what he describes as a “dull engineering class” when someone walked into the class asking for a draftsman. Shook had taken one drafting course in high school, but the thought that registered in his mind was “work.” In the midst of the Depression, someone was offering work, and he volunteered for the three-week lettering project.

As that short project for the Carnegie Institution ended, again by chance, the Mayanist, Dr. Sylvanus Morley, walked into the office, looking for someone to do maps and archaeological drawings. Again, Shook volunteered. As he describes it, one little job led to another, until, before the year ended, he was in the Guatemalan jungle of Petén, at the Maya site of Uaxactún.

Shook was to work for the Carnegie Institution for 25 years, most of it excavating Guatemalan Maya sites. From the first, he was fascinated by Dr. Morley’s stories of the great Maya center, Tikal. His first trip there was in 1934, and by 1937, he and two other staff members of the Carnegie Institution had made a detailed plan to begin excavation and repair in 1940.

Unfortunately, other world events—World War II and then Guatemalan politics—prevented the beginning of the excavation until 1955. By then, the Carnegie Institution had turned its research activities to other areas, and it was the University of Pennsylvania, knowing of Shook’s interest, that invited him to become the director of the Tikal Project.

Our staff at the first Tikal Project season, 1956. (behind) Antonio Ortiz, Ed Shook, Linton Satterthwaite, (seated) photographer George Holton, herpetologist L.C. Stuart, conchologist Paul Bosch, entomologist T.H. Hubbel, and artist-archaeologist Patrick Crocker

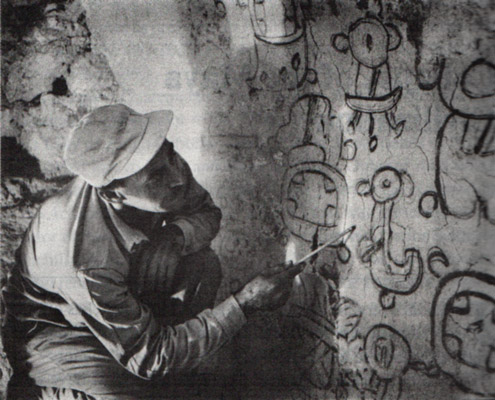

As Shook gathered a team for the Tikal project, he tapped Antigua resident artist-architect-archaeologist Pat Crocker as the Tikal Project artist. Others, including botanists and entomologists, were invited to study the flora and fauna of the greater Tikal area. From their involvement grew the proposal for the Tikal National Park, in order to preserve the wildlife of the area. Shook, with the help of Guatemalan lawyer Adolfo Molina Orantes, presented a national park plan, based on U.S. national park legislation, to the Guatemalan congress. With its approval, the Tikal area became the first national park in Guatemala.

Shook continued as director of the Tikal Project for nine years, until 1964. Under his directorship, many important artifacts, including the oldest stellae known at that time—dating to 328 A.D.—were uncovered. Most important to Shook was the growing body of knowledge of the Maya culture that the artifacts revealed.

Shook himself had once wondered, “Who are these Maya?” Fifty years later, others asked him, “What happened to these Maya?” Shook feels that their collapse was due to overpopulation. The need to feed an ever-increasing population put a burden on the once successful agricultural cycle: Cultivate a piece of land for two to three years, allow it to remain fallow for seven to ten years. Overused land lost its fertility. Food shortages increased unrest among the population.

Leaders began to build ever more temples to appease the gods, removing large groups of workers from food production to construction, which only exacerbated the problem. The great temples of Tikal were probably built within a 100-year period, as were many other Maya temples in other areas. Then, according to Shook, building suddenly ceased, in some cases on buildings under construction, “as if someone suddenly blew a whistle and everyone walked off the job.” The society had disintegrated.

Although Shook took part in many important excavations in Guatemala, his beginning restoration of Santo Domingo Monastery (Convento) in Antigua may be the second-best known, after Tikal, to the general public. Shook gave his wife, Ginny, credit for discovering the piece of land that they bought in 1970 for their home.

Some walls and a colonial chiminea were the only structures standing on it. By the time they purchased the property, the Shooks realized that they were buying two acres of what had once been the largest and wealthiest convent in Guatemala. The section of the convent that had once stood on their property was the student dormitories, tiny cells partitioned every six feet, of the first college in Central America.

Although she doesn’t mention it, author Winifred Veronda may have zigzagged her way to the completion of this book, as Shook says he zigzagged his way through life. A professional journalist, Winifred fell in love with Guatemala after visiting in 1975. In 1983, she earned a master’s in Mesoamerican anthropology and mythology through the UCLA Latin American Center.

She first heard the name Ed Shook from a professor, Henry Nicholson, who observed, “… there’s a retired archaeologist named Ed Shook living in Antigua, Guatemala, who hasn’t published enough and who’s carrying a lot of stuff around in his head and in his field notes. Somebody needs to go down there and get it before it’s lost.”

In 1990, again visiting Guatemala with her husband, Ken, the Verondas were introduced to Shook by a mutual friend. Learning that he had a house for sale in Antigua (not Santo Domingo) they decided to buy it. As a result, they became regular visitors to Guatemala, and friends with Shook. Eventually, Winifred says, she mustered her courage and asked if she might tape some oral history interviews. This book is the result of those interviews.

Although many of Shook’s memories are alive, thanks to Winifred, she ends by reminding us that his field notes await publication.

REVUE BOOK ALERT by Dianne Carofino

Copies of Incidents in the Life of a Maya Archaeologist, as told to Winifred Veronda, may be purchased at the Revue office, 3a avenida sur, #4-B, La Antigua Guatemala (Monday through Friday, 9 a.m.-5 p.m.)

Outstanding work by a truly gifted writer.

Glad we connected Win and Ken to Edwin Shook.

By the way , Ed Shook was also a great tennis player.

Best always. Flo and Greg Silver, Indianapolis

How much is the Book? Thanks Peter Hatch I knew Ed.

Hi Peter — the book is on sale for Q150.

Having worked in Tikal, I unfortunately never met Ed Shook although my late husband had the highest regard for him as an organizer, field director, and archaeologist. He did a superb job of organizing and running the Tikal Project until overthrown in a coup. The work he did in layout out the camp, the work, and the villages for workers, families, students, and tourists remained the backbone of the project for the following nine years and long after the University of Pennyslvania Museum left the field. This account by Winnie Verona gives an excellent insight into the man and the project although it falls short of explaining exactly what went on that brought about the coup. As a student at Penn in the mid sixties, I heard the stories, but none made sense. I knew the players such as Kidder, Satterthwaite and the infamous Bill Coe and it is impossible to figure out what happened back then. What is clear though is that Shook deserves the credit for the success of the project research – some of the most innovative in the world of archaeology. He gave people the freedom to experiment and pursue their ideas and their hunches, and the result was a number of superbly advanced small projects which still remain unmatched in the field of archaeology to this day. One such project, the extensive mapping of areas outside the center of Tikal has just been published by in Europe with the original data available to the general public for the first time.