The Zen of Relation Words

I tell my sons to pack a pocket mirror whenever they travel. Why? So that they, being half gringo and half Guatemalan, can flash themselves a hateful stare each time they toss trash out the window of a speeding chicken bus. (Did I say a speeding chicken bus? Uh, is there some other kind?)

I tell my sons to pack a pocket mirror whenever they travel. Why? So that they, being half gringo and half Guatemalan, can flash themselves a hateful stare each time they toss trash out the window of a speeding chicken bus. (Did I say a speeding chicken bus? Uh, is there some other kind?)

Their half-and-halfness is a legacy of my 16 years of marriage to their mom, a circumstance that obligated me to explore the zenniness of family labels in the Hispanophonie.

My in-law package included enough heads to populate a midsize Dallas suburb; my ex-wife has 57 first cousins just on her dad’s side, and another cuarenta y pico (40-odd) on her mom’s—a hundred first cousins. The census takers long ago gave up on counting her second cousins.

All these people are, or were, my parientes, which means relatives, not parents. OK, so false cognates are nothing new. But if pariente does not mean parent, then what does? The lamentable answer is padre. But were you thinking that padre is the word for father? Yes, that, too, but not in the plural. Mis padres always mean my parents.

This raises a few questions. The esoteric one is: Which word do Bible translators use to tell us that King Jehoshaphat rested with his fathers? These fathers, of course, are ancestors, and so translators accordingly use antepasados. So, in this instance, it is English that equivocates.

The more mundane question is: How do we express parent in the singular? Frankly I do not know. (Write to me if you do.) We can say madre or padre, but the latter may have to be expanded to padre varón unless context removes all fuzziness, as on the forms I filled out each time one of my sons was born. These included sections called datos de ls madre and datos del padre.

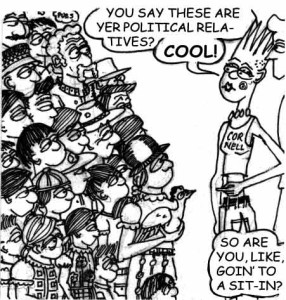

Now I have called my in-laws parientes, but in fact this word only covers my half of my sons’ extended family. Their mom’s half is not my parientes but my parientes políticos. This is what we call in-laws, whether or not they attend rallies or even vote. (But if one’s in-laws are political junkies, does that make them parientes políticos?)

What this means is that while I can call my wife’s nieces sobrinas, I may have to clarify when the person I am addressing points out that my charming niece, Laura Torres, does not look like me. I have to admit that she is “only” my sobrina política.

All is not zenniness, however. In Spanish, we are blessed with the elegant words cuñado and cuñada in place of the unwieldy brother-in-law and sister-in-law.

To make matters better still, Spanish has real words for the spouses of cuñados. Instead of presenting Laura’s father, Enrique, as “the husband of my sister-in-law,” I simply present him as my concuño.

Now to half-siblings and step kin. The former are directly translatable as medio hermano and media hermana. And the step labels are easy if you see them all in one place, since there is a clear pattern. Instead of padre, madre, hermano, hermana, hijo and hija, we have padrastro, madrastra, hermanastro, hermanastra, hijastro and hijastra.

Here are two ways to remember to insert -astr- before the final vowel. This letter cluster looks a lot like the Greek word for star (aster). So if you like your step-relatives, think of them as stellar versions of your blood relations. If not, think of them as space beings from the star system Sigma Stinkus 13.

Now we come to the zenniest label. Your sweetheart is your novio or novia. But upon engagement, a novia becomes a novia comprometida. In practice, this phrase is always abbreviated to comprometida. So far, so good; but on the big day, and on the days prior to it—when she becomes what we call a bride—she reverts to being called a novia. So the continuum of girlfriend/fiancée/bride becomes novia/comprometida/novia. Perhaps, on the home stretch, the bride-to-be is put on probation, being demoted (temporarily, let us hope) to girlfriend status. A better explanation is that Spanish lacks separate words for girlfriend and bride—a zenny omission, since novia serves two poles. It likely recalls an age when all marriages were arranged, a courtlier era when we had fiancées and brides, but no girlfriends.

But I find it in my heart to forgive Spanish for such failings each time I recall that my pal Enrique Torres is my concuño.

Sixty Zen columns now form a unique book, The Zen of Pues, useful to Spanish scholars at all levels. Visit www.ideaquestbooks.com; also available in bookstores throughout Guatemala. Tel: 7762-2022 or www.ideaquestbooks.com