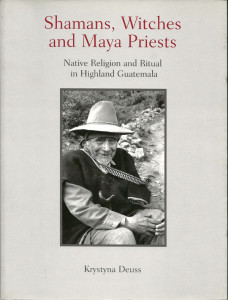

Shamans, Witches And Maya Priests

As the end of the Mayan long count calendar, 2012 has received much recent media attention. Is it receiving the same degree of attention from today’s Maya priests? An emphatic “no” is the answer from Krystyna Deuss, author of Shamans, Witches and Maya Priests.

Deuss has spent much of the past 30 years observing and befriending today’s practitioners of Mayan traditions in the western highlands of Guatemala. “Traditionalists” is her term for these people, who spend large amounts of their time and material goods preserving the spiritual practices of their grandfathers, as they saw and remember these customs.

Deuss made her first trips to Guatemala during the late 1960s, following a post-graduate year of study in anthropology at the University of Vienna, Austria. During that time, her principal area of interest was traditional dress (traje). Her research into the history of traje brought her into contact with cofradías (religious brotherhoods) and Maya priests, and she attended their ceremonies, initially whenever they coincided with her trips to the area, and then on a more regular basis.

When Deuss realized that she was being allowed to participate in rituals no other outsider had witnessed, she decided to leave a historical account of the religious rituals and the changes she observed in them from 1987 to 2002.

Although Deuss hopes that her book will stand as a historical record on which future researchers can build, it is her first person descriptions that make this book enchanting to read. Through her eyes, the reader meets the traditionalists as she meets them, observes their costumbre (Mayan religious ritual) as she observes it, and hears the conversations in which Deuss attempts to understand what she has witnessed. It is these descriptions that draw the reader into the lives of the people she describes.

Deuss first briefly visited Santa Eulalia in the mid-1970s to buy samples of traje worn at that time. In February 1985, with the worst of the civil war past, she returned to document changes in traje, and met Doña Ana, widow of a deceased Prayersayer (Maya priest), as she mentored her sons, Victor and Antonio, as they assumed the past role of their father. As Deuss made trips back to Santa Eulalia over time, Victor learned to speak Spanish, and a grandson worked in the United States, enabling the family to build a two-story house in the center of town.

The reader feels the magic that Deuss experienced as she participated in her first service marking the change of Prayersayers in the little village of Chimban. The service took place the night of Dec. 31, to mark the end of the old and the beginning of the new, and Deuss was first invited to participate in 1987. She describes that ceremony, in the dark, “with just the glow of the fire and candles lighting the faces of the assembled group.”

“It was a magical and memorable moment,” she recalls today.

Deuss makes a distinction between the customs of the traditionalists she observed, who follow the classic Mayan calendar of the Dresden Codex, and the calendar of the “New Age Mayas” as she calls “the young intellectuals who learn about Mayan traditions in a university class.” One of the many differences that she notes between these groups is the calendar they follow.

The “Mayan” calendar taught at the university level is that of the K’iche’, who originated in Mexico and conquered much of Guatemala prior to the arrival of the Spanish. Deuss feels that the K’iche’ presence may not have reached past Todos Santos Cuchumatán, to the area that she has researched. Travel there is difficult even today, and the area is often bitterly cold and covered by clouds. Deuss feels that the Mayan calendar used, and other aspects of the costumbre, may predate the K’iche’.

The long count calendar, due to end in December 2012, and begin again—much as 1999 ended a millennium and 2000 begananother millennium—is virtually unknown in the areas that Deuss has spent three decades studying.

Two calendars are used by the Maya practitioners of the western highlands, the 260-day Tzolkin and the 365-day Haab. The Haab, or solar calendar of 18 “months” of 20 named days, each with a Day Lord of various benign or malevolent characteristics, has a period of five extra days at its end. Spanish Catholic priests who described Mayan customs in the 16th century called these days “unlucky.” Today’s traditionalists still see these days as a “delicate” period when souls depart their bodies. At midnight of the last day, the Maya priest of some towns still goes to a holy place to recall the souls.

Deuss’ fear, as she ends her research, is that “political activists, who organize conferences of Maya priests and invite the press to photograph them sacrificing turkeys, often undermine true costumbre and spirituality … . Today’s Maya activists give courses in divining techniques and furnish their pupils with the K’iche’ version of the Tzolkin calendar, completely oblivious to the fact that in the northwestern Cuchumatanes an older system prevails.”

It is hoped that Krystyna Deuss and the research she shares in Shamans, Witches and Maya Priests will do much to stop the erosion of the costumbre, which has survived in the western highlands of Guatemala.