The Magnificent and Fragile Giant Kites of Sumpango

Kites of November

Written by. Louise Wisechild

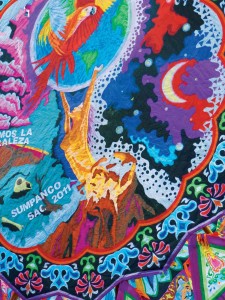

On Nov. 1, visitors travel to Sumpango and Santiago, Sacatépequez, to stand in awe of los barilletes gigantes, the giant kites made specifically for the Day of the Dead in these two Kaqchikel Mayan villages. As large as 20 meters, the size of a six-story building, the kites are decorated in figures, landscapes and messages, resembling enormous murals or mandalas. From a distance it is easy to think that the kites are giant paintings or made of plastic or nylon. In fact, they are collages on a fantastic scale, every image, indeed every part of the kite is made from layers of hand-cut papel de china, the semi-transparent, colored tissue paper often used to line gift boxes or as wrapping paper.

The Day of the Dead is the culmination of between six and eleven months of work for los barilleteros, the kite makers. The kite festival and exhibition on Nov. 1 is the first time the barilleteros themselves see the results of their labor as the sections of the kites are glued together, then mounted on a web of bamboo.

In Sumpango there are 75-80 groups of kite makers, over 600 barilleteros, most of whom are teenagers and single young men. They are from many occupations, including farmers, students, electricians, architects and lawyers. They are willing to work from 7 p.m. to 1 or 2 in the morning Monday through Friday nights and then from 2 in the afternoon on Saturdays until noon on Sundays beginning July 1 and finishing Nov. 1. Barilleteros with 8-10 years of kite-making experience coordinate the making of the kites and teach the younger kite makers the method and the culture of the barilleteros. In addition to doing the actual work of the kites, the barilleteros contribute their own money toward the construction of the kites.

Even standing close to the kites, it is difficult to believe they are not paintings but are actually made of thousands of pieces of paper. Variations of color and shading are made by gluing overlapping layers of colored paper to create figures of people and animals, landscapes and written messages. Because of the fragile nature of the tissue paper, the glue is applied with small paintbrushes. Each piece is then carefully placed and smoothed into position by an experienced barilletero, who is usually working on his hands and knees on a cement floor. A backing of black tissue and clear packing tape reinforces the kite.

Kites measuring six meters or less are flown, sometimes requiring eight men to hold the line as the kite becomes airborne. Many times these kites are seriously damaged in their Nov. 1 flight or in a preflight crash, their beautiful murals shattered by the mischievous wind or by a failure to get off the ground.

These “smaller” kites are traditional eight-sided Guatemalan kites, the octagon making a unique rounded, as opposed to a diamond, shape. This octagon is thought to represent the Maya belief in the four directions: north, south, east and west, with four additional points to form a corona, the crown of the sun. Fringed paper is fixed to four sides of the octagon. The sound of the wind rustling this cut paper is believed to keep away bad spirits. Prayers and messages to the ancestors are traditionally placed on the string of the kite and then are moved by the wind up the string. When the message joins the main body of the kite, it has been received by the ancestors.

The larger kites are not flown, but displayed upright. The mounting of these kites involves securing the kite to an intricate lattice of bamboo and then undertaking the herculean task of hoisting the kite so it is vertical. Families pose for photos, diminished by the size of the kites. Many of these massive kites are far from being octagonal —indeed some of them are so challenging in structure that they are designed by barilleteros who are professional architects and builders.

Following the peace treaty of 1996 and led by a group of highly creative barilleteros, who call themselves “Happy Boys,” the gi-ant kites of Sumpango became increasingly innovative in form and design. In addition to giving their group an English name, they broke free of the traditional eight-sided kite to incorporate open space and improbable shapes into the form of their kites. Other groups followed and also began addressing social issues such as indigenous rights, pollution, violence and the situation of women. Some kites speak to the contemporary meaning of Mayan cosmology using modern images, others affirm the strong cultural traditions of the Mayas, portraying highly detailed scenes, all crafted from colored tissue paper and meticulously glued.

Perhaps more than any Mayan art in Guatemala today, the creation of los barilletes gigantes is an evolving form giving voice to contemporary Maya artists and speaking to the power of traditional community and collaboration. According to a barilletero I spoke with, the tradition of using papel de china for the Nov. 1 kites is over 70 years old. It is interesting that such a slight medium was chosen for such intricate and time-consuming work, but perhaps it represents the nature of life itself, magnificent and fragile.