The Future of the Peace Corps in Guatemala

Anna Zauner received the evacuation notice at 10 p.m. on March 15th, 2020: Have all of your things packed and ready in an hour. “I was 30 minutes from home with nothing packed,” according to Anna, “home” being the highlands of Guatemala where Anna was one of 165 Peace Corps Volunteers (PCVs) serving in the “Land of Eternal Spring.” Due to the global outbreak of Covid-19, over 7,300 PCVs were being evacuated from sixty-one countries.

Departure for Anna was chaotic with many “stops and starts.” After saying goodbye to as many friends as possible in Santa Lucía Utatlán, Sololá, Anna headed to a hotel near the airport in Guatemala City to await a chartered flight that was to depart the next morning. After a sleepless night, Anna and her fellow Volunteers found out that the flight had been canceled due to “restricted airspace.” Restricted airspace! What did that mean? After U.S. embassy officials negotiated with the Guatemalan government, the Volunteers—flanked by embassy and police escorts—headed for the airport with sirens blaring and lights flashing, the multiple vehicle escort something right out of a Hollywood movie. Once the plane lifted off, there was a palatable sense of relief, and a few hours later, they touched down in Miami.

The first thing that occurred to Anna once she returned was that she was happy to be home, but “What about the ones I left behind? When I told my host family in Guatemala and tried to explain through tears that I was hoping to come back but was unsure if I would be able to, they said to me, ‘No tenga pena’ [‘Don’t worry’] for the lack of goodbyes, for leaving the community I pledged to serve for two years. The students I was teaching have been spending their time at home, leaving quiet soccer fields and classrooms bereft of laughter. I hope the lecture I gave on positive youth development through life skills will protect students going forward. There was so much more, which I did not get the chance to address: substance abuse, reproductive health, and mental health for starters.”

Anna Zauner is one of a long line of Peace Corps Volunteers (PCVs), who first arrived in Guatemala in 1963. Since then, almost 5,200 have served in Guatemala, providing assistance to rural and urban families in cooperation with governmental and nongovernmental organizations. Anna arrived with 134 other volunteers working in health, youth, and food security programs. Anna was a youth development specialist.

Much has changed since I was a PCV in Guatemala in the 1970s. The world has become more complex and dangerous, leading to a greater focus on security issues within the Peace Corps, something I became aware of while interviewing for a Guatemala Country Director’s position in 2014. About three-quarters of the way through the interview I realized that I had not been asked one question about program development or monitoring and evaluation. All the questions related to potential security threats.

Later that evening after my interview, I met the Program Director for Peace Corps Guatemala at a reception. He told me that the Peace Corps office had been moved from Guatemala City, the country capital, as well as the largest city in Central America, to a small rural site outside of the city because it would be closer to the rural areas where the volunteers are based, although others have since confirmed that it was due to security concerns.

I also learned that Volunteers were not allowed to enter the capital due to concerns for their safety. Volunteers could no longer jump on “chicken buses” like I had used frequently as a Volunteer (customized school buses decorated with exotic paintings and colors) but had to use Peace Corps-provided shuttles to and from their sites. The Peace Corps staff now included security personnel, and when I contacted a Volunteer about collaborating with a local Rotary International program in her area, she told me she would find it difficult to connect with them because she had to be home for a 6 p.m. curfew! Although informed that I qualified as a potential Director, I decided not to pursue the opportunity.

What Do Guatemalans Think?

I turned to award-winning Guatemalan filmmaker and friend, Luis Argueta, for a Guatemalan perspective on Peace Corps in his country. Luis, who received the “Harris Wofford Global Citizenship” Award from the National Peace Corps Association (NPCA), spoke to the attendees of the Peace Corps “Connect to the Future: A Global Ideas Summit” held in Austin, Texas in July of 2020. Some of his comments are included in the Fall 2020 issue of “Worldview Magazine,” in an article titled, “A Time to Reflect.”

Luis and I have a special interest in the emigration/immigration conundrum. He has paid close attention to forced displacement, forced migration, and asylum seeking, and asks a very timely question, “…even if borders today are closed, once they open…people will be forced again to leave their homes. What is the Peace Corps to do at a time like this? I think it is to go and work at the very basic community level and help better conditions that are making it impossible for people to stay at home and be with their family and prosper and be healthy.”

He goes on to say, “At the same time that we self-reflect on our role and our privileges, and the privileges of Volunteers, we should look at the historic ties between the host countries and the U.S. … the U.S. government is not issuing visas for my fellow Guatemalans to travel to the U.S., while there is a threat of cutting visas even for exchange students who pay full tuition at U.S. universities, let alone temporary workers who pick the crops in the fields of the U.S. So, we must be conscious of these contradictions. And we must relearn the history between our countries.”

He ends with the fact that although Peace Corps Volunteers reached home safely during the pandemic “… this took them away from a place where they had committed to work—and where people without that privilege, that choice, had to remain in a more vulnerable position.”

To that point, the Director of the school where Anna Zauner worked says that her students are studying online and some of them have reached out to Anna on their English assignments. But some students have revealed that working from textbooks alone is difficult and some feel they “aren’t learning.” To date, these students don’t know when their school will reopen, which is the case throughout Guatemala.

The Peace Corps in Guatemala

Peace Corps Director, Jody Olsen, was tasked with the unenviable job of evacuating the 7,300 around the world. It must have been painful, as the Peace Corps has been in her “blood for 54 years” (she served as a volunteer in Tunisia in 1966). Her comments on the future of the Peace Corps, made on July 18, 2020, began with, “We will be stronger for what we have been through together. The Peace Corps mission of world peace and friendship is as relevant today as it was in 1961.”

Peace Corps Guatemala Director of Programming and Training, Jeremy Boley, is still in Guatemala and gave me a heads-up on the status of the Peace Corp’s return: “Peace Corps Guatemala is diligently elaborating the strategy to return Volunteers to Guatemala. This includes close coordination with our partners in host country agencies as well as closely monitoring the progression of the pandemic. We are looking forward to welcoming Volunteers into all four of our programs, including Community Economic Development, Agriculture, Youth in Development, and Health.”

He also confirmed that the security of Volunteers is “of utmost importance and maintaining an Emergency Action Plan and having a system to monitor the location of Volunteers are indispensable tools in ensuring the well-being of our Volunteers.”

Recent natural disasters that precipitated deadly landslides and flooding, which destroyed crops, impacted over 1.7 million Guatemalans. Government data shows

acute malnutrition among under-fives rose by 80% last year in comparison to the previous year. With this in mind, Jeremy stated “Since it takes time for communities to recover from the effects of these events, Volunteers may find that their community development skills are needed in these areas. Agriculture Volunteers, for example, may assist their work partners in training on soil conservation techniques that maximize infiltration during heavy rains and reduce flooding. With respect to migrant caravans [heading to the U.S.], Volunteer efforts in our Youth in Development program encourage youth to stay in school and develop job-related skills to improve their employment prospects in Guatemala. Our Community Economic Development Volunteers will support income-generating activities that encourage development and growth within Guatemala. These efforts promote alternative pathways to migration.”

A Time for Reflection

Although 134 Volunteers were forced to evacuate, close to 5,200 returned Peace Corps Volunteers (RPCVs), whose lives were impacted by their service in Guatemala, remain a positive influence on the country as well as the Volunteers who will return. My experience as a Volunteer indicates that no matter how effective I was, I learned more from Guatemalans than I was able to teach them, and what I learned would motivate me to continue supporting the most vulnerable populations in any way possible. One way to accomplish this is to fulfill the third objective of the Peace Corps, which is to promote a better understanding of other peoples on the part of Americans. The Peace Corps Writers Group lists 327 RPCV authors who have written two books or more and they have generated somewhere around 1,000 memoirs.

One such author, Mark Brazaitis, has written eight books including “Stories from Guatemala: The River of Lost Voices,” winner of the Iowa Short Fiction Award. He also wrote the script for the award-winning Peace Corps film, “How Far Are You Willing to Go to Make a Difference?” The best memoir among RPCVs/Guatemala would be Ellena Urbani’s, “When I Was Elena.” She has written for “The New York Times” and her stories have been selected for inclusion in a number of collections and books about her Peace Corps service.

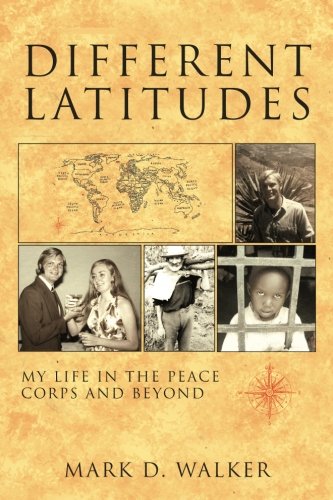

Much of my book, “Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond,” took place in Guatemala. I totally agree with Luis Argueta’s observation about being conscious of the relationship between the U.S. and its host countries and I included a chapter entitled, “Guate mala Guate peor,” which starts with a quote from writer Eduardo Galeano, on “Rigoberta: The Granddaughter of the Maya.” “This book relates to the dreams and nightmares of a land pulled apart from the army, rapped by businessmen, lied to by politicians, despised by doctors.” The CIA led a military intervention of Guatemala in 1954 with the overthrow of Arbenz and the elimination of important changes like land reform, destroyed the opportunity to deal with the serious inequality and poverty facing most Guatemalans, especially in the highlands, and is the basis of many of the country’s social ills today. These publications and the many presentations and materials written by other RPCVs, help educate the public in the U.S. about the realities and needs of Guatemala and help inform U.S. policy makers. Also, RPCVs can do things that the Peace Corps can’t as a government agency with certain norms placed on it by our country’s foreign policy.

What Have We Learned?

The Peace Corps, like our country, has changed a good deal over the last 60 years. When President Kennedy asked, “Technicians or engineers, how many of you are willing to work in the Foreign Service and spend your lives traveling around the world? … But on your willingness to contribute part of your life to his country, I think will depend on the answer whether a free society can compete.” But as author and RPCV Paul Theroux points out, “It is impossible to imagine any politician — anyone at all — saying that today.” And yet the urge to serve, to travel and learn a new language will assure that some of the evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers will return and many more will apply to volunteer in the “Land of the Eternal Spring.” This desire to serve and the actual economic downturn and impact of COVID-19 in the U.S. will accelerate the number of individuals willing apply and serve in Guatemala. And based on my interview with the Peace Corps Program Director, Jeremy Boley, I think that the organization is positioned to deal with some of the special challenges facing them today, including the growing levels of hunger and malnutrition experienced by Guatemalans as well as issues like climate change.

Over the years, these 5,200 RPCVs have formed lifelong relationships and a series of organizations that continue to benefit Guatemala. Overall, 245,000 RPCVs have formed 180 affiliate groups, which are part of the National Peace Corps Association. These individuals and the alliances they’ve formed with international groups take many forms and shapes. I’m a board member of “Partnering for Peace,” which promotes shared programs between Peace Corps Volunteers and Rotary International, and which has 1.2 million members worldwide and a strong presence in Guatemala. I’m also a member of “Friends of Guatemala,” which has provided scholarships benefiting children for over thirty years. Larger chapters like the affiliate in Washington D.C. have over 4,000 members and develop partnerships with many non-governmental organizations.

No doubt, Returned Peace Corps Volunteers and some of the groups they’ve formed, along with the International community, will need to support local leaders’ efforts to hold their government officials accountable by sending them to prison for corruption, as is the case with former President, Otto Perez Molina, and his Vice President, Roxana Baldetti. And push for the return of U.N. agency CICIG (a powerful U.N. backed commission formed to investigate corruption), which exposed over 60 corruption schemes, implicating officials in all three branches of the Guatemalan government. These alliances must support and attempt to protect the lives of local leaders and advocates fighting for basic rights, push for more influence in the government and in the workplace as well as local rural alliances that promote economic development and education.

For the last fifty-seven years, the Peace Corps has been part of the development process in Guatemala. Now that the Peace Corps is preparing to send Volunteers back to the field, they’ll need to retool in order to meet such challenges as the growing malnutrition, climate change and a lack of a basic healthcare needs. Simultaneously, Returned Peace Corps Volunteers and their affiliate groups will need to continue telling the stories of Guatemalans and supporting the best programs and local leaders they can identify. Given the enthusiasm of the incoming volunteers and the commitment of the Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, in conjunction with local and international alliances promoting human rights and development, I have great expectations that the Peace Corps can help Guatemalans meet the new challenges of the future.

About the author Mark D. Walker

(MillionMileWalker.com)Mark Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala, 1971-1973, working on fertilizer experiments with small farmers in the Highlands. Over the next 40 years, he managed or raised funds for many international groups, including Food for the Hungry and Make A Wish International and wrote about those experiences in Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond. He is also a contributing writer for the Revue magazine: Maya Gods & Monsters; The Making of the Kingdom of Mescal; Luis Argueta – Telling the stories of Guatemalan Immigrants; Luis Argueta: Guatemalan Filmmaker Recipient of a Global Citizen Award and Traveling in Tandem with a Chapina. His wife and three children were born in Guatemala.

Go to MillionMileWalker.com or write the author at Mark @MillionMileWalker.com

REVUE magazine article by Mark D. Walker