Wild Cats of the Middle Realm, Central America

The Biogeographical Realm of Middle America stretches from the Mexico’s Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the north around to southern Panama.

This narrow land bridge, which joins the two regions, has been the major dispersal route for species moving north and south, most often as the result of climate change caused by major ice ages and the relatively short, warmer inter-glacial periods like we are in right now. As the weather gets colder many species migrate toward the more pleasant equatorial zone and when the heat is on species extend their ranges toward the poles.

So over the eons innumerable multitudes of species—both plant and animal—have used the Middle American land bridge during their tireless search for more hospitable climes. If global warming progresses as predicted by the majority of climate scientists, we can expect a lot of species movement in the coming years both in latitude and altitude.

And, it might be said that the millions of humans who leave their traditional homelands in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador to make their way north looking for better opportunities are simply the latest wave of biological migration across the isthmus and northward in search of warm lush meadows brimming with honey-money.

All the preceding paints the picture of a land where there has been a constant mixing and co-evolution of species all contributing to Guatemala having one of the Earth’s most diverse and varied fauna and flora. Here we find coyotes sharing biomes with cacomistles, jaguar territories overlapping mountain lion hunting grounds, and trogons and oropendolas alongside migratory ducks and grebes from Canada wintering at a Highland lake or coastal lagoon.

The region’s diversity extends to felines, and there are six different species that inhabit the forests and jungles of Meso-America. So let’s take a look at them.

First, the jaguar, the undisputed king of the rainforest. Known to scientists as Panthera onca, the majestic jaguar, the largest extant feline in the Americas, can weigh up to 300 pounds. Jaguars range all the way from southern Arizona down to the Amazon. And it is accurate to call the jaguar “king” because no other forest denizen would ever dream of challenging one (with the exception of certain parasitic creatures, like screw worm, that can give the big cat hell at times).

The jaguar roams around its territory, which is often more than 10 square kilometers. When feeling a bit peckish, jaguars dine on a delectable armadillo or fat, juicy paca. Or when tree climbing, long-distance foraying, or extended swimming brings on real hunger, they may invest a little more effort and take a deer, wild pig or tapir for dinner. In all the literature related to jaguars it is usually asserted that these big cats are extremely shy and virtually never bother humans.

I related this idea one time as I was sharing a beer with a geologist who had done extensive surveying all over the remote Amazon basin. When I told him that there was no evidence of jaguars attacking humans he laughed and said, “Of course there is no evidence … all the evidence was digested by the tiger!” To this I will only add that my ex-mechanic in Belize, a man by the name of Bruce, was killed by a jaguar as he returned to his jungle cabin one night.

Years ago, as I was walking down a remote track near Hopkins in southern Belize, I suddenly felt the “hairy eyeball” and glanced over and down to my left. There, not more than a stone’s throw away, was a beautiful black jaguar looking at me intently. Our eyes locked for a long second and then he just casually turned away and walked into the shadows.

The adrenaline rush didn’t even begin before the encounter was over. But as brief as it was, that image—and feeling—of the big black jaguar looking into my eyes is etched into my memory forever. I imagine that he was thinking: Should I or shouldn’t I?

By the way, black jaguars, often misunderstood by locals to be a separate kind of animal, are simply the rarer melanistic phase of the same Panthera onca.

The next largest feline of the region is the mountain lion, Felis concolor, aka cougar, puma, panther or catamount. Lions can be found in just about every habitat from coastal mangrove swamps right up to high-altitude pine and cloud forests. In my experience they are much bolder than the jaguar and sightings are much more frequent.

We also know that they most defiantly will go after a human from time to time. A few years ago, I was hiking along a remote jungle track in northern Belize and suddenly saw, way down the road, two beautiful lions just standing there watching me. They did not run away; they did not seem scared of me at all.

This caused me to feel more than a little nervous. For some reason, call it second sight, I had taken the precaution that day of bringing a canister of grizzly bear repellent, something I very rarely do. Armed with this defensive weapon, I felt pretty safe. The lions paced around and kept eyeing me, and I imagine that they were thinking about what to do with me.

At that moment, if I had attempted to flee, I am confident that they would have pursued me, and there would have been no escape. But acting boldly, I started shouting and waving my arms and finally they disappeared into the bush. I felt pretty nervous as I made my way back to my camp on the escarpment. I felt that they were following me although I never saw them again.

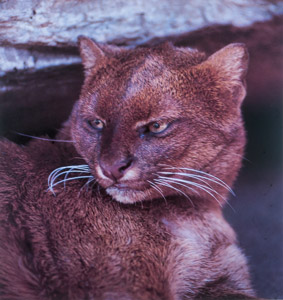

Next up is the sleek jaguarundi, Felis yagouaroundi, sometimes referred to as the “little otter cat.” These smaller felines also range widely and can vary in color from dark gray to reddish brown. Very shy and retiring, the jaguarundi have adapted better to human presence than their larger cousins and are reviled by the region’s campesinos because they rob chickens.

I have seen them hunting in pairs, running through the jungle, and making high-pitched whistling sounds back and forth. They dine on a wide variety of small mammals and birds, bird eggs and even snakes, including poisonous vipers.

Middle America has three smaller spotted cats all of which look pretty similar: the ocelot, Leopardus pardalis, which can get up to 80 or 100 pounds in the Amazon but in our region rarely exceeds 30 to 40; the margay, Leopardus wiedii, which is generally smaller than the ocelot and considered to be more arboreal with a semi-prehensile tail; and the oncilla or little tiger cat Leopardus tigrinus, which ranges from Argentina and the Amazon basin up to northern Costa Rica and looks pretty much like a small ocelot with a slender build and narrower muzzle.

Finally, we have the bobcat, Lynx rufus, whose present range is from northern Canada down to Chiapas in southern Mexico. There have been unconfirmed reports of bobcats from remote areas in the Cuchumatanes Mountains of Huehuetenango and San Marcos departments in Guatemala.

Unquestionably one of the most beautiful felines on Earth, the bobcat tends to be very shy and sightings are rare even where they are relatively common.

To ensure that these beautiful creatures have a future it is urgent that more be done in Guatemala to protect the forests. On a recent month-long trip to El Petén department I was dismayed to find nearly every protected area invaded by hunters, illegal settlers and loggers, despite the forest’s “protected” designation by the government. Some recent brochures produced by INGUAT, the Guatemalan government’s tourism agency, are emblazoned with the slogan: Guatemala: Mega Diverse Forever!

But the way things are going, Guatemala will soon be a wasteland of Mega Extinction. Anyone who doubts this let me just testify that when I first visited this magic land in 1973 the Petén rainforest was virtually uninterrupted from the Mexican border down to Isabal. Today there is very little forest left between Flores and Río Dulce, and ALL the protected areas are being invaded.

In a recent meeting with Dr. Eduardo Cofiño, who has been involved with the development of Guatemala’s northern jungle province for decades, I asked him point blank what the future holds for the largest bloc of tropical rainforest north of the Amazon basin. “The way things are going, it’s pretty much all going to be lost,” he lamented.

“The situation is exacerbated by the fact that Guatemala has the highest birth rates in the Americas and, as you have seen, the government has failed to develop any real strategy to save the forests … but job number one is getting our population stabilized as soon as possible, and then find sustainable ways for people to exist. As long as our campesinos are hungry they will exploit whatever is at hand … and that means the forest. No one blames people who are simply trying to feed themselves and their families.”

I have concluded that the only hope to save the forests is by stimulating the citizenry to get involved with the defense of nature. For this reason, and as a last-ditch effort, we are launching our Green Gospel project to see if we can get all the churches of Guatemala preaching the green message to their parishioners and followers.

Perhaps if the people become convinced that it is the will of God that we take care of nature, God’s Creation, then we might make some headway in defending her. If people of all faiths dedicated just one day every week to cleaning up and protecting the environment, tremendous things could be accomplished.

The Green Gospel needs to be preached high and low, in the public square, in the schools and in the churches. The message is very, very simple, so that even a child can understand. To be healthy we all need a healthy environment. For Mother Nature to be healthy, she needs her natural forests and all her other sacred natural places to be preserved … and LOVED!

REVUE’s “ROADS TO ADVENTURE” text/photos by Capt. Thor Janson, navigator / explorer, facebook.com/nubliselva

Thank you for this fascinating and important article. I like the Green Gospel as an idea in raising awareness. I would also suggest that Guatemala look to Costa Rica which has successfully leveraged conservation and nature tourism against mighty corporate interests such as mining and deforestation. Tourism can provide many more jobs to the local communities and provide an incentive to conserve natural resources. Tourists also contribute to the preservation of indigenous arts by buying the fine work available here. I think that if INGUAT more effectively promoted the natural beauty and the indigenous culture of Guatemala, as Costa Rica and also Mexico have successfully done, conservation might then be seen as essential for both sustainability and economic growth.