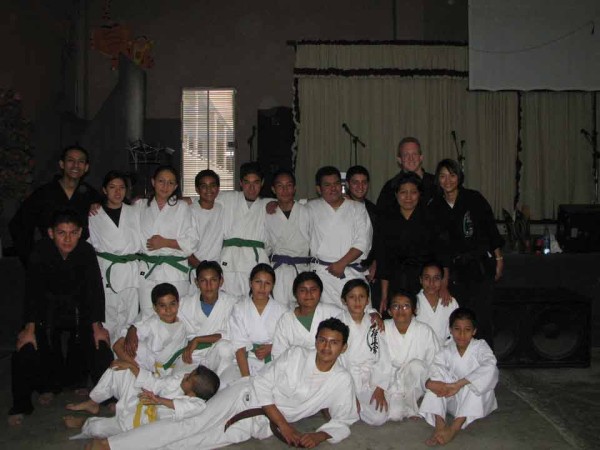

Karate Kids in Church

People go to church for many reasons: to worship, to study scripture, to sing hymns, to seek healing, to earn a black belt in karate. Wait a minute—to earn a black belt?

Now you have heard it all. Churches do some unchurchy things to help bring in money, like holding aerobics classes, bake sales and bingo nights. But karate?

First of all, the karate lessons at Shalom Baptist Church are gratis. Not only that, but they go all the way up, for those who persevere, to Black Belt. The only catch is that they are not for just anyone. And therein lies the next surprise.

The students are street kids, or potential street kids, from Guatemala City’s toughest quarter, zone 18.

Guatemalan Nathan Hardeman, son of missionaries from Georgia (U.S.), knows these kids. For him, karate is a vehicle for imparting success, an element of Shalom’s crusade to break a cycle of fatalism that predestines so many from zone 18 to truncated lives.

Hardeman has heard the litany countless times: “I’m from zone 18. I’m stupid. I can’t do anything.”

Hardeman answers: “You can do something.” And some already have.

The karate program is not about violence, but violence abatement. It is the handmaiden to the development of personal responsibility, self-control, punctuality, follow-through and other virtues.

“These are lacking in zone 18,” Hardeman says, “where the social order has broken down.” Who is to blame?

“The men,” he says. “They start out born into fatherless households. Without role models, they perpetuate the incidence of teen pregnancy and out-of-wedlock births. They learn no structure when young, and thus cannot promote it when older. If they get much older.”

Many do not. Shalom Ministries, of which the church is part, has ministered to so many that it needs no government statistics. Hardeman has a photo of a group of 10 adolescents taken in 1998; he knows what became of each boy. He can do a similar rundown on a picture taken 11 years later of another 10 boys; for these, Shalom is making the difference.

“Boys need to grow into good men, that is the way out for their families.”

“These boys are still young enough,” he says. “They haven’t had a chance to go bad. But all but two of the first bunch ended badly. They’re dead, disabled from violence or drugs, in a gang, or in prison.” Nine boys in the second photo are doing well; the 10th could go either way.

“Boys need to grow into good men,” he adds. “That is the way out for their families.”

The karate not only draws boys. Girls are even more welcome.

“Girls growing up in zone 18 need a way to defend themselves, and this gives them that,” Hardeman says. “A girl with a black belt is far likelier to avoid growing up too soon, and to have a real go at life.”

Neither boys nor girls study karate as an isolated discipline. Nor is the curriculum itself conventional. They get spiritual training as well, including a foundation in the biblical imperatives to love one’s neighbor—even one’s enemies. If you can disarm your enemies, the reasoning goes, it is easier to love them.

But there is more, including standard academics and athletics. Hardeman, with the help of various organizations, built a soccer stadium in the especially rough, if ironically named, neighborhood of Paraíso II.

It is more than a pastime venue; teamwork is practiced there. But the centerpieces of the mission are its clinic, which serves 450 patients a day, and its school, which enrolls 750 students from impecunious families.

Most of the students attend Shalom Temple, the Baptist congregation led by Pastor Alvaro Perdomo.

Nathan Hardeman, 36, grew up in Quetzaltenango. He admits that, until he was 22, he had “no desire to help others.” But that year he was tapped as a translator for a mission team bound for zone 18.

“I saw extreme poverty and hopelessness up close, for the first time,” he recalls.

The karate instructors are long-term volunteers with American Bushido-kai Karate Association in Oklahoma. The first ones arrived to work with Larry Jones’ Feed the Children mission.

“Originally,” Hardeman says, “they came to help distribute food. But they quickly saw the potential of starting the karate school here.” Hardeman was a novice karate teacher himself at the program’s inception.

“Two days before I taught my first class,” he recalls, “I knew nothing myself. But the next day I had a crash course. After that, I taught what little I knew.” Today both Hardeman and wife Claudia are Black Belts.

The style of karate taught is Okinawan. Only the martial and choreographic aspects are taught; the Eastern mysticism normally included with karate instruction is omitted. A course within the course is the practice of a kata, a choreographed routine that tells a story. Completing a performance requires discipline and perseverance, to say nothing of good attendance. Kata mastery results in improved self-esteem and a heightened ability to control impulses. It also helps to winnow out the occasional bad apple who manages to enroll for wrong motives.

“A girl with a black belt is far likelier to avoid growing up too soon, and to have a real go at life.”

“[Our karate laureates] never go on to become troublemakers, ” Hardeman boasts. “It hasn’t happened even once.” The reason, he explains, is that those with bad motivations either change or they wash out. Those who make it through get assistance to complete their vocational training.

This holistic approach to improving the individual extends to improving the students’ household.

“Rarely,” Hardeman says, “is it enough just to train up the individual. We discover that, to keep him off the street and on track, some changes need to be made at home as well. The whole family may need transformation.

The mother may need a repair to her home, to make it safer. Or younger siblings may need vitamins.” For such ends, Shalom Temple offers not only material support, but also nutrition and home economics classes.

Nathan and Claudia are laying foundations for their own mission. Property has already been acquired, but no ground yet broken, for a special boys’ home in the department of Sacatepéquez.

“Some boys must be entirely removed from their environments,” Hardeman explains. “We’ll put them with normal families, where they’ll receive modeling from married, responsible house parents, while pursuing their studies.” The house parents may have their own children. The Hardemans’ program is named Engadi Ministries, after a cave near the Dead Sea where King David, anointed but not yet crowned, hid from King Saul.

“Young men without direction came there and attached themselves to him,” Hardeman explains. “In time, they became the king’s ‘mighty men,’ the officer corps listed in 2 Samuel 23. That’s what we want for our boys—to become like David’s mighty men.”